On the Lasting Allure of Moonlighting

The screwball comedy genre emerged kicking and screaming and wisecracking in American cinema because of the censorship crackdown in 1934, which wouldn’t allow for any sexual license between men and woman on screen. Now a man and a woman would battle with each other verbally before becoming a couple or after becoming a couple in crisis, and Howard Hawks was the director who brought this idea to full flower in Twentieth Century (1934), where John Barrymore and Carole Lombard have some prizefight-level verbal and physical bouts, Bringing Up Baby (1938), where Katharine Hepburn leads paleontologist Cary Grant out of his shell, and His Girl Friday (1940), where Grant and Rosalind Russell spar verbally at an incredible rate of speed.

Screwball comedy was a short-lived vogue; by the mid-1940s it had more or less run its course. Peter Bogdanovich revived it for What’s Up, Doc? (1972), close to a remake of Bringing Up Baby with some meta touches, but it did not fully come back until the TV series Moonlighting in 1985. Writer-producer Glenn Gordon Caron had been told to do a “boy-girl detective show,” and when he sent his pilot script for Moonlighting to Cybill Shepherd, she at once recognized that he had written a Hawksian screwball comedy and told him so. Shepherd had been Bogdanovich’s romantic and creative partner through most of the 1970s, and she was steeped in the greatest movies of this genre; she loves Carole Lombard so much that she always carries some sort of copy of My Man Godfrey (1936) around with her in her purse.

Antagonistic chemistry with Shepherd was what was needed for her leading man on Moonlighting, and that kind of chemistry was obvious when they auditioned Bruce Willis, who was an unknown at that time. Male network execs didn’t think he was believable as a love interest for Shepherd, who had been a top model just like her character Maddie Hayes; she was famous as a great beauty and had starred in three classic 1970s films, The Last Picture Show (1971), The Heartbreak Kid (1972), and Taxi Driver (1976). But a female exec at ABC stunned the room when she said that to her Willis had allure as a “dangerous fuck,” and this helped to get him cast.

The pilot of Moonlighting, which aired in 1985, doesn’t have the zing of what was to come; it plays today like a fairly typical TV movie of that moment. Shepherd’s Maddie Hayes loses all of her money and is about to liquidate the Blue Moon Detective Agency but becomes intrigued by Willis’s bad boy David Addison, and there are scenes in this pilot that don’t play well now. David calls Maddie a “cold bitch,” and she calls him a “sissy fighter” who doesn’t know how to throw a punch to her liking, and this makes them seem less attractive than they were supposed to be at the time.

But once Moonlighting got a rapid-fire dialogue rhythm going in the office between Maddie and David, it became clear right away and it is still clear now that something tantalizingly uninhibited, sexy, and edgy was happening between the characters and between the actors, and this had that sense of romantic possibility that had made the best screwball comedies great. This was even clear to the king of the screwball comedy genre himself, Cary Grant, who phoned Bogdanovich to say of Shepherd, “You were right about her all along.”

The mystery plots on Moonlighting were there as a framework only. What kept most people tuning in was the banter between David and Maddie, which was played at such top speed that it irritated some people who weren’t hip to it and intrigued by it. The best scenes between them were generally the opening jousting matches in the office and especially the scenes where they were driving, which could be as wildly verbal as possible because they didn’t need to block anything and Shepherd and Willis could read the dialogue on the dashboard or elsewhere if needs be. (To their credit, it’s very difficult to catch them reading because they are so fully in the moment.)

Willis’s facility with the high-speed delivery of dialogue is unerring, even show-offy. Shepherd’s style is nervier, more vulnerable, like her idol Lombard, with a racing sense of danger to it. The set-up was classic screwball: con man/hipster David was going to get Maddie to loosen up and have some fun, and underneath was the dynamic that he was a disappointed, Bogart-ish romantic and she was going to make him believe in love again. David and Maddie are in their thirties: not young, but not middle-aged, experienced and a bit bruised, but still open to the thunderbolt of desire. In the first three seasons, there’s no place I’d rather be than the offices of Blue Moon Investigations with Maddie Hayes and David Addison, who are like dream parent figures, and I hate real-life offices.

In her 2000 memoir Cybill Disobedience, which is nothing if not candid, top-dog alpha blonde Shepherd, who plays by no rules but her own desires, writes about the mutual attraction between herself and Willis at the start of the series and how they almost did something about it but thought better of it after a heated make-out session at her place. That delayed or put-off gratification was key to their chemistry on the show, and they both knew it. Shepherd was at the height of her beauty, particularly in the season two episode “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice,” which was shot on black-and-white film by their cinematographer Gerald Finnerman, who used diffusion lenses for many of Shepherd’s close-ups elsewhere, a practice that caused some comment and which she good-naturedly mocked on a later episode.

As a little kid, I was dazzled by the entrances of Maddie Hayes into the Blue Moon offices week after week on Tuesday nights: she was a cascade of blonde hair, shoulder pads, flowing silk jackets, camisole tops, belts, skirts with slits, and flats, and this extremely alluring look, which to child me epitomized 1980s glamour, was created by costume designer Robert Turturice. Most 1980s glamour hasn’t aged well, but the look of Maddie Hayes is as sumptuous as ever. Yet the maintenance of this image took a lot out of Shepherd, who had to get up at 5AM and spend hours putting it together, whereas Willis could just basically roll out of bed.

The hours to shoot Moonlighting were punishingly long and uncertain, and Caron always had new pages for his actors at the last minute. The scripts he wrote were double the length of standard scripts for one-hour TV shows, and Shepherd’s energy began to flag; even Willis eventually asked, “How long are they going to make us keep doing these?” The usual season for a network show then was over 20 episodes, but Moonlighting only managed 18 in its second season and 15 in its third.

Yet that third season produced classic episodes back-to-back: “Big Man on Mulberry Street,” which had a musical number directed by Stanley Donen, and “Atomic Shakespeare,” a riff on The Taming of the Shrew done in iambic pentameter. It was on the musical episode that tensions came to a head between Caron and Shepherd, who questioned the nature of Maddie’s dream about David directly to Donen, who did not respond. Willis charmingly does his best to keep up as a dancer here, and Shepherd herself, who belts out tunes in the black-and-white episode, understands movement enough to get a lot out of one shoulder roll and a toss of her hair.

Shepherd has often been demonized as the reason that Moonlighting ended the way that it did, but if you read the full testimony of everyone involved, as detailed in Scott Ryan’s very enlightening book Moonlighting: An Oral History (2021), it becomes clear that Shepherd and Caron had clashes in which sometimes one of them was right and the other wasn’t, and vice versa. When it comes to the musical episode, it feels to me that Shepherd was in the wrong creatively. It does feel like Maddie would dream about David being heartbroken and needing her to come in and be the dream woman and heal him, and this actually turns out to be true, so Maddie’s dream is a premonition.

Shepherd does some of her best acting on the show in “Big Man on Mulberry Street” in a monologue that she plays half in shadow where Maddie haltingly speaks to David about her feelings for him. This scene is so effective because it is the opposite of the verbal fireworks the series was known for, and the shadows on her face allow Shepherd to totally let her guard down and enter into the delicate emotion of the writing in a way that makes it feel touchingly real and defenseless.

But then Caron made a crucial mistake with his female star while shooting a later scene in this musical episode. As detailed in Ryan’s book, Caron was frustrated with Shepherd, for valid reasons, and he made some kind of remark that got a laugh from the crew at her expense. She shut down completely, and it is visible on her face in this scene with David’s ex-wife that Shepherd herself is upset and not fully able to engage in character as Maddie. This episode was a creative height for the series and also the moment when it definitively collapsed behind the scenes.

The following episode, “It’s a Wonderful Job,” asks a lot of Shepherd, and she delivers, particularly in a scene where Maddie is on the phone and is told by her father that a relative has died and she has let him down by not being there for her. Shepherd is a Hitchcock-style actor in that she doesn’t “do” a lot or scribble thoughts or emotions all over her face; she keeps her face open for when a scene like this occurs, and she allows the emotion to come naturally, and this is very moving on this episode because it is like an actual reserved person getting upset rather than an actor showing off. Shepherd/Maddie often looks down when she is feeling some kind of pain or grief, as if she wants to attempt to protect herself, but of course in life this is not always possible. Shepherd does not have the kind of stage actor technique that she can fall back on to get her through a scene like this; she has to actually put herself through it.

As meta as Moonlighting could be, what keeps it alive now is the reality of what Shepherd, Caron, and Willis provided, three talents who hit at the right moment for maximum combustion. Willis never did anything better than Moonlighting; look at the hilariously fluid way he does “immature” physical schtick behind Shepherd as they walk through the office in the set-up to the season two episode “My Fair David” if you want to see how inspired he can be. And in Shepherd’s case, this series was the best possible showcase for all of her talents, comedic, musical, dramatic.

Maddie and David finally slept together in the season three episode “I Am Curious…Maddie,” and even though there were great difficulties (Shepherd was pregnant now with twins, Willis had broken his collarbone in a skiing accident, and the two actors were deeply fed up with each other), the passion looks real between them as they hungrily kiss to “Be My Baby.” I can remember watching this episode when it aired, and it made me very eager to be an adult and not a kid so that I could get to do such fun adult things.

Caron has said that the show could have continued after the lead characters finally had sex, and he is likely right about that, but Shepherd’s pregnancy meant that Maddie had to be pregnant, and a child for Maddie and David kills the nature of the show, just as a child for Nick and Nora Charles in the Thin Man films eventually killed the very attractive banter and raillery between Nick and Nora.

As far as I’m concerned, Moonlighting should or does end on the cliffhanger episode that finishes season three, in which Maddie and David must continue to have great sex with each other as a car they are in starts to roll downhill, the perfect visual metaphor for their chemistry. Willis went on to be a movie star after the show ended, often in action pictures, and Shepherd went on to another hit show with Cybill, a sitcom where she was set up to be upstaged by a performer, Christine Baranski, who is 100% technical.

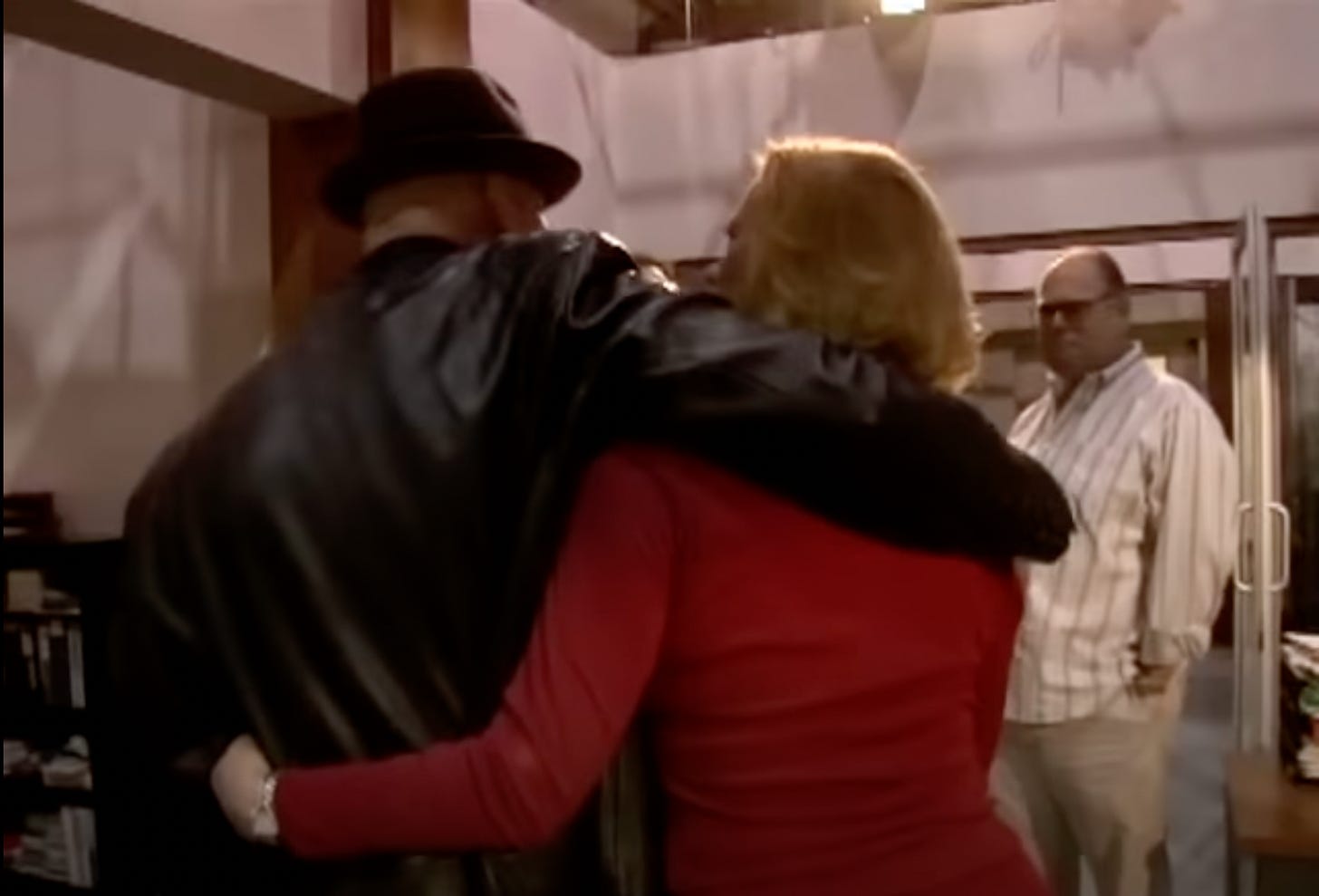

When a Moonlighting DVD was released in 2006, Caron, Shepherd, and Willis got together to reminisce, and there is a beautiful and telling moment at the end of it where an embrace happens between the stars that is sweetly tentative at first and then “ah, why not?” affectionate, and all with Caron looking on as an observer and creator who knows that his creations are finally outside of his final control.

Link to Scott Ryan’s book is here: https://www.tuckerdspress.com/product-page/moonlighting-an-oral-history