“I am a big sentimentalist, even if I don’t seem that way,” said Marcel Carné in an interview to promote the laserdisc release of his masterpiece Children of Paradise (1945). “In terms of my private and intimate life, I’m very vulnerable.” In photographs, Carné has warm and humorous eyes, but there are some shots where these eyes look very sad, very romantic, and very “love me.” Carné made around 20 films, and he often spoke about how he had 40 or so other projects that never came to fruition, like a man describing an unrequited love.

He was born in 1906, and his mother died when he was five. As a young man, Carné wrote film criticism and praised the work of F.W. Murnau for its expressive camera movement. He began to assist director Jacques Feyder, and he made his own first movie, a short called Nogent, Eldorado du dimanche (1929), a vibrant “let’s see what I can do” debut where his youthful ardor came into play for lingering shots of beautiful male athletes and divers; at one point Carné even lowers his camera to appreciate the lower body of a male rower, and he catches two young men staring with desire at the women who pass by.

There were two figures in France that the gay Carné might have modeled himself on: the dandyish Marcel L’Herbier, who made epic films that almost always showcased his lover Jaque Catelain, and Jean Cocteau, whose sense of the dreamlike and the erotic must have influenced Carné as his career went on, especially in the way Cocteau showcased his own lover Jean Marais. But this sort of influence would have to wait.

Carné became famous for the seven films he made from 1936-1945, from Jenny to Children of Paradise, and those pictures have risen and fallen regularly in the estimations of critics and cinephiles. They were shot on enormous studio exteriors, and they relied on screenplays by Jacques Prévert and star performances from Françoise Rosay, Jean Gabin, Arletty, Jean-Louis Barrault, Michèle Morgan, and others. Carné was a nervous man and not what he termed a natural leader, and the style of these movies that made his reputation is artificial in a way that uses artificiality as a mask and also as a means of control. The fatalism of the tone of the writing of the Carné-Prévert movies is a pose that hides the more tender romanticism and sexuality that Carné would have liked to have brought to his work.

There is something of this quality in Gabin’s one-eyed teddy bear who eventually gets shot by police in Le jour se lève (1939), but an unexpected flash of rear nudity from Barrault and a shot of a young Jean-Pierre Aumont in what could be fetish gear in Drôle le drame (1937) are the only signs that the Carné of his experimental debut short is still there; otherwise, his desires had to be very subtle. It is possible to watch Children of Paradise many times (and watching it many times over a lifetime is one of the great pleasures of life) without picking up on the relationship between two of the male characters. “It’s obvious Lacenaire sleeps with Avril,” said Carné, according to Semiotext(e) publisher Hedi El Kholti.

The novelistic intensity of characterization in Children of Paradise and the way that the three men in love with Arletty’s Garance eventually all meet and clash is an enormous Jamesian achievement, particularly because Carné was shooting this hugely ambitious project during the last days of the Nazi occupation of France. The wise smile of Arletty has been the emblem of Carné’s cinema, but also remember the look of uncertainty on her face when Garance leaves Jean-Louis Barrault’s Baptiste at the end of the film, disappearing into the crowd, life going on like some whirligig around her that swallows up her most devoted admirer. If you don’t already know, it would be difficult to tell that the director of this movie of movies was a homosexual, but the romanticism that believes in a great sexual encounter between Garance and Baptiste is even more of a tip-off than any implied sex between the male characters.

It was only in the early 1950s, when Carné’s reputation was in decline, that he was more open about his point of view on life, and this new openness came about largely because of his feelings for Roland Lesaffre, a young actor 20 years his junior who became his Galatea and his great friend and companion. The nature of this relationship was not conventional. This is how Lesaffre wrote about it in his 1991 memoirs (thanks to Phoebe Green for this translation):

“This man, this man of the common people like myself, had become indispensable to me,” Lesaffre wrote. “I loved him. He offered me a gruff and decorous tenderness. In his company, the world was good…Marcel would become the accomplice and the witness of my life, as I would be his. He would respect my life as I respected his. It was during the writing of the scenario of Thérèse Raquin {1953} that I became accustomed to loving him. That habit has lasted for 40 years now.”

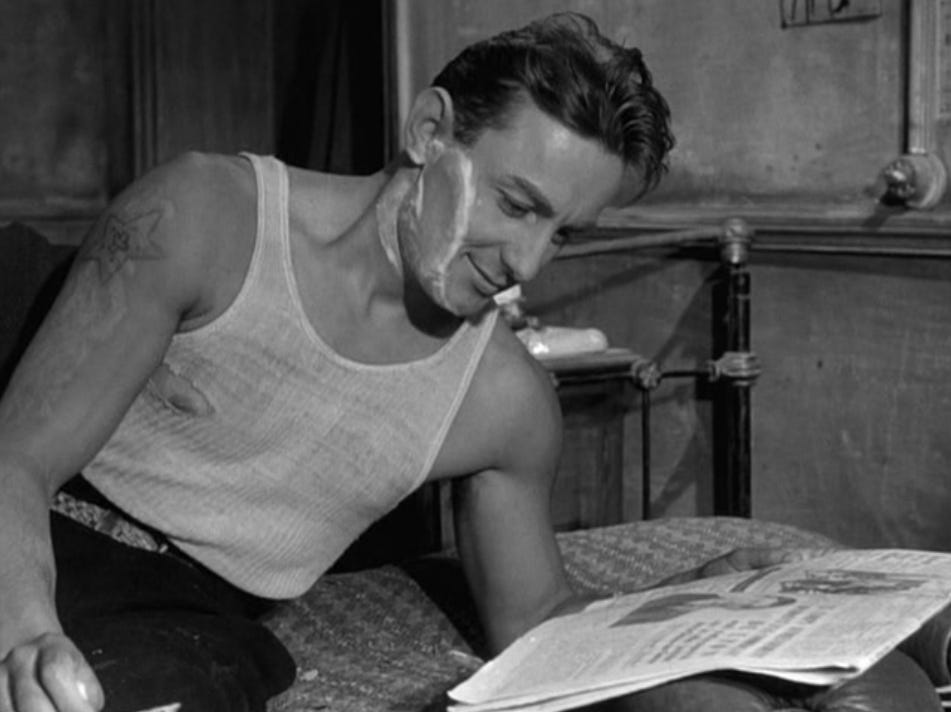

Lesaffre had played some bit parts in Carné movies before being given a blatant and very sexy showcase for both his looks and talent in the last third of Thérèse Raquin, which so obviously comes to a halt for this extended reverie on Lesaffre’s appeal that star Simone Signoret seems openly irritated by it on screen. In a scene where Lesaffre is shaving in a tattered t-shirt and he turns to profile with just a bit of shaving cream still on his face, Lesaffre is like a Jean Cocteau drawing come to life. The glorification and fetishization of his looks by Carné is very uninhibited here and specific, for the t-shirt Lesaffre wears is torn so that when he reclines on a bed only one of his nipples is visible. His blackmailer character rides a motorcycle, and he seems both innocent and dangerous; when slapped around by Raf Vallone, Lesaffre chooses to look surprised and impressed, a memorably humorous choice.

There is an amazingly erotic shot of Lesaffre’s face as he dies that looks like something from the late silent era, something fantastical and intense. It is safe to say that no director has ever made their desire and love for an actor as poetically expressive as Carné does for Lesaffre in Thérèse Raquin. There are shots in that movie of Lesaffre that Josef von Sternberg might have admired and understood.

Carné went even further with L’air de Paris (1954), in which he dared to make his star Jean Gabin into an older man who is very clearly in love with a young boxer played by Lesaffre. The tone here is dispassionate when it comes to observing the repression of Gabin’s character and the frustration of his wife, played by Arletty, who didn’t even sleep with him on their wedding night. There is a shot of Lesaffre here from behind in skimpy white underwear that qualifies him as a Greek god from all angles, and his hetero-ish vulnerable roughness is contrasted with a fashion designer character named Jean-Marc (Jean Parédès), who is gay in the way of the comedy relief queens played by Franklin Pangborn in the 1930s.

Carné had a late financial hit with Les tricheurs (1958), a portrait of wayward youth most notable for its tenderly satirical first half hour in which Laurent Terzieff’s Alain is portrayed as radically open-minded. At a party with his friend Bob (Jacques Charrier) where they observe a young gay man named Danny negotiating with his hetero-ish lover, Bob says he prefers women, and Alain says that he does too but that he doesn’t “have any prejudices” against men sleeping with men, a radical stance for 1958. “But you’re not…” says Bob, to which Terzieff’s Alain says, “What if I am?”

Even better, when Alain talks to Danny, who says that he is faithful to his male lover, Alain shoots back with, “You expect me to applaud this ugly bourgeois sentiment?” So not only is Alain open-minded about sex, but he sneers at a young gay guy who is trying to imitate hetero respectability. Alas, we are supposed to reject Alain as the film goes on, but the impact of Terzieff’s beatnik magnetism in the first third of Les tricheurs has made its impact.

Carné did not have good luck with projects past this point, and Lesaffre receded into supporting roles in his movies. In the early 1970s, Carné kept running out of money and took three years to finish La merveilleuse visite (1974), a fragile film based on an H.G Wells source about an angel fallen to earth in which Carné’s camera glorified the nude body of slender blond Gilles Kohler, who is found by Lesaffre’s character on a beach and wanders around a rural setting.

It could be that this all had some private meaning for Carné and Lesaffre, as if they dreamed of getting away from that stylized city of Carné’s 1930s films, the city that hurts and knocks, for a rural utopia in which a pure sex object who looks like Kohler has no need of clothing. A freed Carné lingers on Kohler’s beautiful stomach and saves shots of his perfectly shaped behind as high notes for his simplified mise en scène. The premiere of La Merveilleuse visite was loyally attended by Arletty and Michèle Morgan, but it was barely distributed and remains difficult to see.

When Carné was on the jury of the Venice Film Festival in 1982, he tried to sway his fellow jurors to give the Golden Lion to Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s homoerotic Querelle, which seems to have made a profound impression on him, not least because its stylized sets recalled his own, but with the pornographic openness of Cocteau’s erotic drawings; when he couldn’t get a prize for the film he withdrew from the jury.

Carné was set to make a feature with Juliette Binoche called Mouche in 1992, and there is a photo of him on the set with the loyal Lesaffre by his side, but ill health forced him to withdraw. He died in 1996, and when Lesaffre died in 2009 he was buried with Carné, his mentor and great friend. Children of Paradise is a height in the cinema and of course in Carné’s own career, a dream, perfection, without one false step. But his later work where he got to express himself more openly should not be overlooked but looked over.

Happy you're enjoying the articles here, Alan---:)---and yes, I have seen all of Carné's films---I wanted to focus more on his later movies---but I should look at "Hotel du Nord" again--

Hello Dan - Thank you for Stolen Holiday, which I discovered about 3 months ago, and all the great essays you've posted so far. I particularly loved reading your insight into Marcel Carne, and the gay undertones of his movies. However, there is a Carne work in which that undertone becomes visible to all. I'm guessing someone might have mentioned this to you already, but have you seen 'Hotel Du Nord' (1938)? This is a fabulous picture - great characters, played by wonderful actors, and the setting, and set, are unforgettably brilliant. Among the ensemble of characters we get to know is a very out, young, non-stereotypical gay man - he doesn't play a lead role but the two or three scenes in which he appears are amazing for the non-judgemental depiction and the almost surreal appearance of a gay man in a 1938 mainstream / art-house film! Anyway, happy new year and keep up the good work! Alan.