When I read on Facebook on September 30th that the Broadway matinee idol Gavin Creel had died at the age of 48, something happened to me that is difficult to describe. I was stopped in my tracks, stunned, and I wanted to stay with that. Almost immediately I thought to myself, “Don’t let go of this feeling, don’t forget this,” and even, “Don’t let go of him.” This was partly because the circumstances of his death were unusually cruel and unfair. Creel had only been diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of cancer in July, and so the hammer came down on him very quickly and out of the blue.

I started watching videos of Creel singing on YouTube, and I also began watching all the rather long interviews and podcasts he did over the years, a little over 20 years worth, from 2002 to today, and even in the first few days I was doing this I started to think, “There will come a time when you run out of these, when you can’t see or hear anything new from him.” There might be some more, but I seem now to have come to a kind of end of watching him and listening to him. And so I felt a deep need to try to make sense of what I saw and heard.

I am haunted by Creel. I find myself repeating his name during the day when I am doing other things. I desperately want to bring him back, to help him somehow, to make him smile. There came a point, of course, when I thought, “OK, this is officially unhealthy, what you’re doing,” but I dismissed this fairly quickly and thought, “Oh, please, unhealthy is your middle name, keep going with this.” Make some meaning of this. Notice this as comprehensively as possible. But I kept putting off writing something about this, about him, because I was afraid that I wouldn’t do him justice somehow, but I was also afraid that in writing about Creel and what happened to him that I would be finally pushing it away, setting it aside, which is ultimately what writing does.

I only saw Creel perform live once, in the revival of She Loves Me in 2016, and I vividly remember his swaggering physicality, the way he took the space with his long arms and legs and relished the most outsized effects he could get with movement. He never made a feature film, and he only appeared on television a few times, as a sweetheart hotel employee named Bill in two TV movies based on Kay Thompson’s Eloise stories in 2003, and then as part of a gay couple in a two-part episode of American Horror Stories in 2021. The distance in tone between those two credits spaced so far apart tells a story about the way Creel was cast in his youth and the way he could be cast in his maturity.

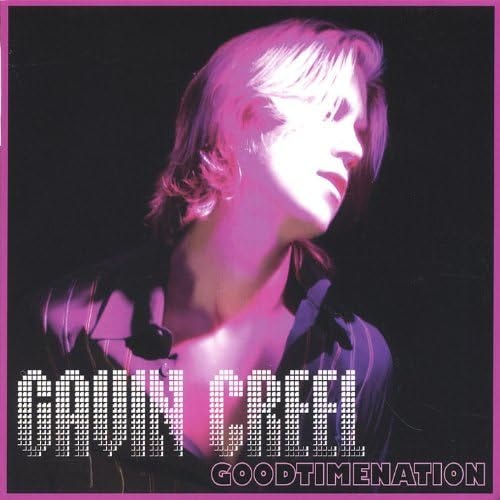

Creel first came to prominence on Broadway in 2002 in the musical Thoroughly Modern Millie, where he was a leading man for break-out star Sutton Foster, and he had two songs in that 1920s-set show, “What Do I Need with Love?” and “I Turned the Corner,” which showed off his seamlessly expressive tenor singing voice, with its lustrous high notes. He took part in the ill-fated Stephen Sondheim musical Bounce in 2003, still with slicked-back hair and period clothes, and he played Bert in Mary Poppins in London. At the same time, he recorded a pop album called Goodtimenation in 2006, for which he co-wrote very cheerful and sexy songs with Robbie Roth. It was recorded independently, without the help of a label, and so it didn’t make the impact that Creel had hoped for.

Creel was told that he was “too old, too gay, and too Broadway” by record execs. That was the thinking in 2006, when he was 30. I think that Creel knew that if he had released an album like Goodtimenation in 2024, and if he had been in his twenties or younger, that it could have been a hit for him and propelled him into another realm of show business. For he loved pop music; his teenage idol was Whitney Houston. In watching videos of him, Creel is impressive in his Broadway credits, but he is most himself and having the most fun, giving the most pleasure to himself and his audience, when he is singing solo with a small band, doing pop-ish versions of his signature Broadway songs mixed with his own songs.

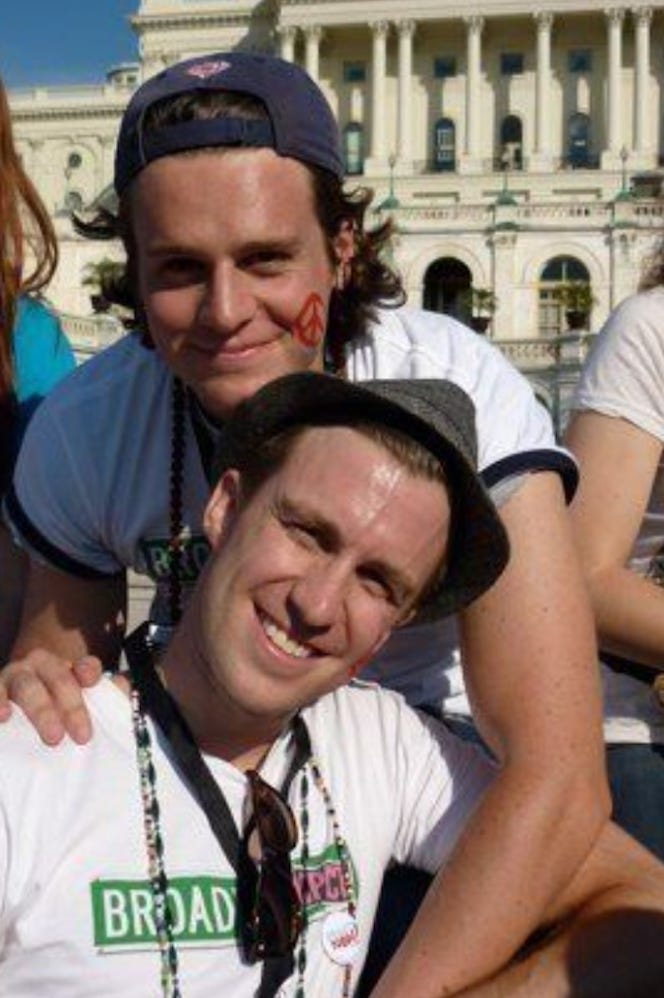

Creel made a key transition when he starred in a much-loved revival of Hair on Broadway in 2009, which unleashed his own need for political action and a more radical honesty. He came out of the closet professionally (no small thing at that time), and so did his boyfriend Jonathan Groff as they marched for gay marriage in Washington.

Creel spent three years on tour and in London with The Book of Mormon, a show in which he got many laughs with his very uninhibited physical behavior that signaled the “I’m full of myself” hubris of his character; he was playing close to 20 years younger than his actual age in this production, and very convincingly. And then he won a Tony for best featured actor in the colorful Bette Midler revival of Hello, Dolly! in 2017, where his tenor was as bright as ever on “Put on Your Sunday Clothes.” He played the Wolf and the Prince in a successful revival of Into the Woods in 2022, and then Creel created a show for himself, Walk on Through: Confessions of a Museum Novice, which he was still tinkering with when he was taken ill and taken out so suddenly. That show was partly about his own midlife crisis, which he was extremely frank about in interviews.

The pandemic of 2020 and 2021 was a very rough time for Creel in which he went through a bad break-up and started to doubt everything about himself, which he spoke of with candor in the interviews he did leading up to his death. It was clear that Creel was in a transitional period, and it was painful for him, but there was still also his youthful sense of possibility underlying everything he said. Creel had always represented youth on stage, and surely his energy would have always been youthful had he lived into his nineties like Dick Van Dyke.

What struck me again and again as I listened to the late interviews and podcasts he did was how Creel was so open about his massive insecurities and how much he needed love and reassurance. This is not unusual for an actor, but what was unusual about him was how much he very much needed to give out love and reassurance to others in return. He was famous for being sweet and loving to everyone, to collaborators, to fans, and maybe this came partly from his religious upbringing in the Methodist church, which also scarred him deeply because of his sexuality. Sometimes I would get enjoyably exasperated watching his interviews and think, “Say something negative! Stop being so 100% sweet all the time!” But all his effort in this area touches me very much. In her online tribute to him on September 30, Bette Midler called Creel “radiant,” and that’s a very good word to describe him. Giving off light, radiating joy offered up for us.

There was a video I watched on YouTube where Creel is promoting Hair and a female journalist strikes a pose in a door in tight clothes and says she wants to “join the tribe,” and I’m afraid her behavior falls under that now-dreaded category: “inappropriate.” But Creel’s reaction to her is exemplary. He stands there and takes in her energy and takes in the things underneath this energy that are driving it: pain, insecurity, a need to belong to something, everything. And so of course he can’t reject it. He reassures her without in any way leading her on, and a balance like that couldn’t be any trickier.

Creel is adorable in his various interviews with Paul Wontorek for Broadway.com through the years, and there is one moment from their 2012 interview where Creel says that if he dies and goes to heaven that he hopes to go out and do Hair again, that show that he loved the most. There were quite a few moments like this in his interviews where a bit of my breath would be taken away because I knew something that he didn’t, that he was going to die too early.

There is footage of him from July of last year where he sings the Troye Sivan song “Rush” with his band in a small venue, and it broke my heart because by the time I saw it I knew just how much Creel had wanted to be a sexy gay pop star like Sivan, and how that category did not exist when he was young. I was fully aware, as Creel was, that if Creel had been born 30 years later, he could have fulfilled this dream of his.

So here he is, close to 50 and just a year before his death, sexy and lovably youthful and just slightly tense (whereas in his musical comedy performances he is so smooth), but unwilling to let go of this earlier version of himself, the version that released Goodtimenation in 2006. I love Creel here just as much as I love him when he is so ultra-confident in what he is doing, as in the “Miscast” series for MCC where he gets to explore some dynamic sexual chemistry with Aaron Tveit in their duets.

In the long podcasts he did as he promoted Walk on Through, there is a desperation about his need to receive love and give love out in return. Finally there is a podcast he did with the actor Bobby Steggert that is dated July 17, 2024 in which they discuss the concept of shame for around an hour. I don’t know if he had been diagnosed yet when he recorded this, but it comes so close to the end for him that it feels like a last stand. It is very painful because Creel discusses all kinds of hurts from his youth that still feel fresh to him all in a rush, with piercing urgency, as if he is on a ship that is sinking, and he wants to rid himself of this stuff, this poison, before he goes under. And as I listened to it, I thought, “I can’t help you…I couldn’t help you, and I can’t help you.”

Only a few months before, in April of 2024, Creel was singing ABBA songs for the 2024 MCC “Miscast” show, and his authority and inventiveness as a performer makes me break out in smiles of happiness whenever I re-watch this; he’s so exciting as a singer because you never know what he might do with his body or his voice to give pleasure to his audience. He’s such a ham! The little brother who will not be ignored. The performer who wants each and every audience member to love him, specifically, and he’ll interact with every last one of them if he needs to, and he needs to, God bless him. Religion hurt Creel, but when he is at his best, he is feeling the spirit, in his own pagan way. I can’t be sad when I see him here, so close to the end. Katharine Hepburn once said, “Life is an enormous opportunity,” and Creel took that opportunity by the horns in every sense.

Creel was a classic leading man who would have been cast in golden age musicals, too, but it was the rock musical Hair that was his favorite, the production that meant the most to him as a performer and as a human being. There was something mischievous and Puck-like about him that found its best home in that piece about 1960s liberation and pacifism and radical love being extinguished.

I should try to end this piece with some last line that could try to sum up Creel’s life, his achievement, what he wanted to do, what he could have done, what he meant to the people lucky enough to know him, the people lucky enough to simply talk to him at a stage door, but that would be false. That would be a way of letting him go, of wrapping him up and putting him away, of letting him recede. And I don’t want to do that. I can’t do that. I want to thank him for waking me up. I needed this waking up.

I had and have the usual thoughts about someone like Creel cut down in his prime while truly rotten people just go on and on, but I don’t know how to follow that up. I want to give this more meaning. And I want to reach out to him. As I watched and listened at such length, I kept thinking that if I could interview him for an hour that I would know exactly what to say to give him pleasure and make him smile and get him writing more songs with enthusiasm. I know now all of his insecurities and all the things he needs to hear, wanted to hear. Maybe it wouldn’t be enough; maybe his need for things like this could not be satiated for long. But maybe it would have made him feel good for the rest of the day, and maybe into the following day. I wish I could try that.

Let’s not let him go. Here is some footage from the end of his production of Hair, when his character has been put into a uniform and buzz-cutted and his friends cry out for him as he is sent off to die in Vietnam:

Here is a video of Creel singing “The Rainbow Connection” to little kids on a cruise in 2008:

And here is his final text to his songwriter friend Benj Pasek:

A piece about Creel’s work and about my reactions to it isn’t enough for him. I have never felt like what I do or try to do is so inadequate to the occasion as I do now, with this lost man, with this subject. There is a little bit of relief in having written this, but not much. So I won’t try to sum him up. I’ll just light a light on him and keep the door open. I won’t let this go. I won’t forget this. It’s a part of my life now, and I welcome it, even the painful parts. Welcome. Gavin Creel.

Ray Allen, very happy to read that. I figured there must be other people who were affected like this.

Thank you so much for this. I was affected very similarly & have been doing the same thing: poring over every scrap of interview/podcast available, marveling at what a wonderful human he was, wishing I could have known him, wondering why such bright lights are taken so unfairly. It’s comforting to know I’m not alone in those feelings as someone who didn’t know him personally. 🩵