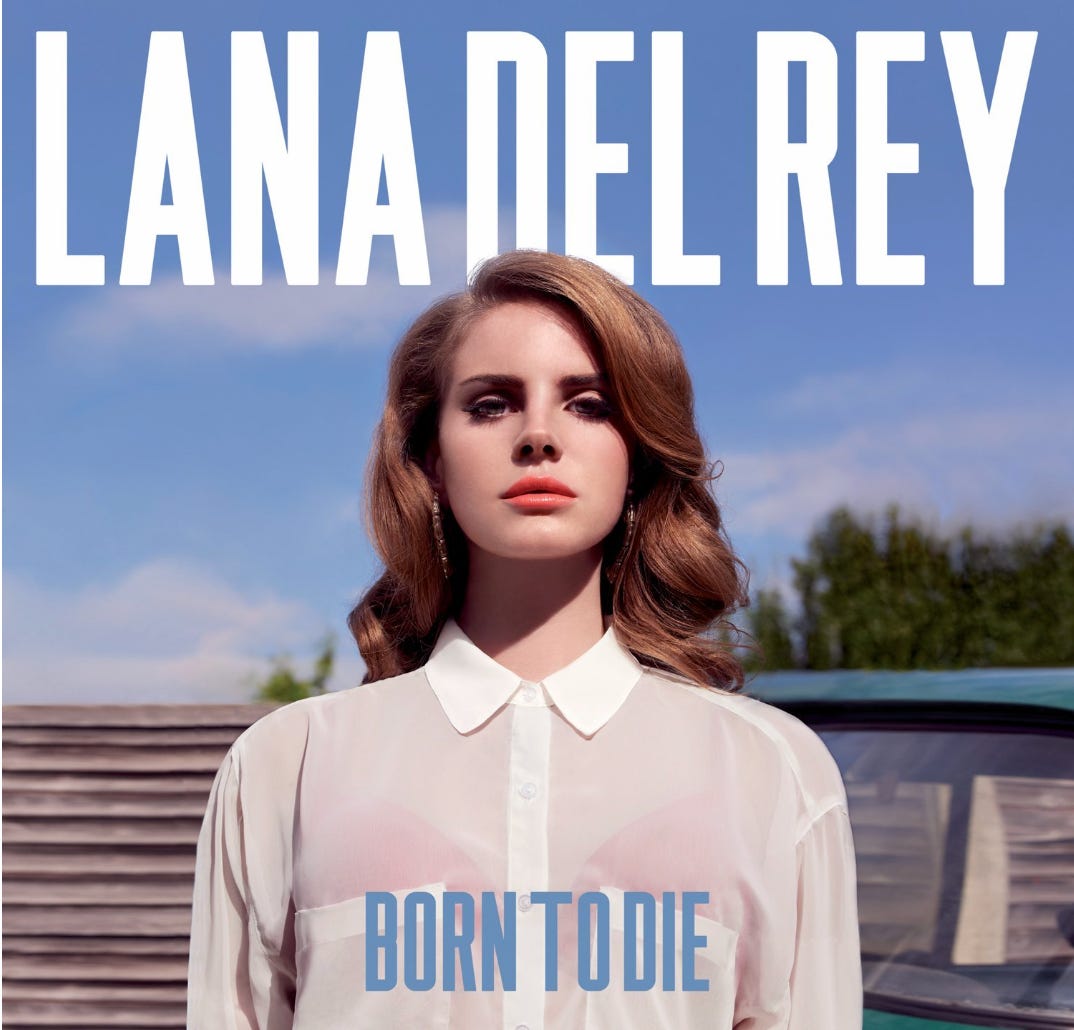

When she first emerged around 2012, I was drawn to the morbidity and studied, bargaining-chip sexuality of Lana Del Rey. I would listen to her album Born to Die over and over again that summer, and when the expanded so-called Paradise edition came out, I would listen to what amounted to another album to go along with it.

Eventually I discovered that Del Rey, who was born Elizabeth Grant in 1985, had recorded material for a first album in 2010 that had been withdrawn, but I found that on YouTube, where it still resides. I was particularly stirred by a track called “Mermaid Motel,” which must be the ultimate stripper song, with old-fashioned stripper bump beats so insinuating that even the most prudish person might be compelled to start doing their own striptease act while listening to it.

“You call me lavender, you call me sunshine,” she sings for the chorus of “Mermaid Motel,” and that “you” in her early songs always seems to be a powerful older man for whom she is exhibiting herself with great and gloating pleasure, and the charge of this was very politically incorrect. “You say, ‘Take it off,’” she croons, “take it off,” and Grant/Del Rey hits the “t’s” like a machine gun (one of the things I like best about Del Rey is that no matter how much she slurs or moans her lyrics you can always hear her crisp consonants at the ends of words). She’s the queen of the gas station here with her king-sized cup of coffee, but she has her hoity-toity side, too.

The part of “Mermaid Motel” I love best is when she suddenly takes on a different Britney Spears-ish voice to say, “Heavy metal hour on TV.” There is something about the way she drawls this line out that captures a whole world of American life, the life of truckers and waitresses and factory workers, drinking beer, eating junk food, taking pleasure where they can. And then there’s that hot key change for “You call me lavender, you call me sunshine….”

Del Rey is aware of her own curated beauty, and in what is still her best song, “Young and Beautiful,” a single released for the soundtrack of The Great Gatsby (2013), she wonders if her man will still love her when she is no longer young and beautiful. In the video for that song, Del Rey presents her sculpted profile to the camera and offers a chillingly forced smile, and she is both nakedly romantic here and emotionally naked: “Dear God, when I get to heaven, please let me take my man.” She has created her own small kingdom, and she sticks to it.

Around this time Del Rey made her notorious appearance on Saturday Night Live where she couldn’t seem to pick a vocal register to sing in for her song “Blue Jeans.” She was trying to sound sexily husky here, and then she started to sing much higher, and this all seemed panicked and absurd; what made it worse was that Del Rey seemed to be tensely judging herself the whole time, which is why watching her sing live can be so agonizing.

But her failure to sound like what she sounds like on her records won her some sympathy, too, and the following week on SNL it fell to Kristen Wiig to do a send-up of Del Rey that somehow managed to be supportive and sensitive. “I think people thought I was stiff…distant…and weird,” Wiig’s Del Rey said. “But there is a perfectly good explanation for that…I am stiff, distant, and weird…it’s my thing.”

Del Rey is a recording artist, and live performing is hard for her. In her early videos, she seemed like a girl in her bedroom experimenting with make-up and wigs and “looks,” a 2010s Internet music star with 1960s eyeliner and Priscilla Presley hair. The sound on Born to Die is lush, the melodies intricate, with all kinds of secret compartments, and so of course she appealed to people who for one reason or another have to keep some of their lives secret. And people who are intense. She’s sexually liberated, and she wants to die; it’s a good start.

“Let me kiss you hard in the pouring rain/you like your girls insane,” she sings on the title track of Born to Die, always aware of how she might be coming off to the men in her life, the older men who might sweep her off her feet, and the young, emotionally inaccessible men who play video games. She can sing about “my man” and say the word “honey” in a waitress-like fashion, and this persona of hers feels not so much old-fashioned as fashioned out of bits of the past to make a new voice; she felt like an original, whatever the various charges of inauthenticity being hurled at her. Born to Die was harshly dismissed by many establishment music critics, but their reaction looks particularly prudish and out-of-touch now.

Del Rey worries that she won’t see her lover “on the other side” on “Dark Paradise,” and her concerns keep drifting to the metaphysical, the big questions. “Kiss me hard before you go,” Del Rey sings on her hit song “Summertime Sadness,” and so always with her there is leave-taking, and anxiety over what lies ahead of her. “Nothing scares me anymore,” she claims on that song, a signal that many of her lyrics are the exact opposite of what Del Rey seems to be feeling and thinking while she sings them, a disconnect that gives them their creative tension.

“Heaven is a place on earth with you,” she sings, so romantically. “They say that you like the bad girls, honey/is that true?” During my Del Rey period, I asked a good female friend what she thought of her, and this friend said, “She’s a dirty girl.” It was not said judgmentally, or admiringly, but more in a neutral sort of way, and I understood what she meant. To me, I would have said it admiringly.

Del Rey was writing about the pleasures of being seen as a sexual object and seeing herself as a sexual object, with a bad reputation for being insane, a bad girl, a dirty girl, and there was a protective glamour to that position. It felt more honest than the “I’m empowered” pop music that was coming from other young female stars that seemed so hypocritical, a marketing ploy to sell sex without any introspection about what that means.

Del Rey wandered into some pretty dicey areas at this time in describing these sorts of moods, it has to be admitted. She had met Harvey Weinstein and put this lyric in a song called “Cola”: “Harvey’s in the sky with diamonds/and he’s making me crazy,” and she now omits his name if she sings this song live. That is also the song where she claims her vagina “tastes like Pepsi-Cola,” which still makes me laugh, admiringly.

Del Rey’s work is a mood, a trance, and that trance of hers brings me back to a golden period in my life, from 2012 to around 2016 or so; she put out more albums after Born to Die, and I liked parts of them, but I kept coming back to that first official album and her Lizzie Grant album from 2010, and even some of the tracks she did in the late 2000s under the name May Jailer for an abandoned album called Sirens.

“You say I’m like the ice I freeze,” she sings for “Brooklyn Baby” on Ultraviolence (2014), and she does have her icy/imperious side, which became increasingly apparent on both this record and Honeymoon (2015). The strings she uses on these albums are still lush and foreboding, and her melodies can still wrap us up in a luscious sort of melancholy, especially the doomy-yearning “Salvatore” on Honeymoon.

But then Trump became president and everything went to hell, and Del Rey’s reaction to all this was one of cryptic anger often dissolving into a near non-verbal haze; she started singing a lot about her frustration with immature younger male lovers. Her song “13 Beaches” on the creatively messy Lust for Life (2017) is very sad, but with these very poetic lyrics: “In the ballroom of my mind/across that county line.” I kept singing those lines to myself after I heard them; they felt just right.

Her 2019 record Norman Fucking Rockwell was met by wide acclaim. “She couldn’t care less, and I never cared more,” she sang on NFR, and that contradiction and fracturing of identity pinpoints how far Del Rey is from mainstream thinking. I have to admit that Del Ray lost me more than a bit with all the experimental-to-formless material on the three albums that came out after that, two in 2021 alone. But maybe that’s because I loved 2012 and hated pandemic-internment-camp 2021, and Del Rey’s expected songs about “my man” and waiting on table couldn’t reach me in that solitude.

Then again, Del Rey herself said to Rolling Stone: “Blue Banisters {2021} was more of an explanatory album, more of a defensive album, which is why I didn’t promote it, period, at all. I didn’t want anyone to listen to it.” Which is attractively perverse, and a little schoolteacher-ish. The usual Del Rey contradictions. David Lynch was a fan, telling Harper’s Bazaar in 2023, “She tells a story in her music. She gives a mood and a story and a way to think, and she paints a picture in your brain.”

I would love to be won back. Del Rey has a country-tinged album set for release, and on the singles for it she seems to have found religion following her 2024 marriage to a boat tour guide named Jeremy Dufrene, and so at least she is changing and moving forward. I thought at the time of her first official record that Del Rey was one of the few pop stars who could age in a way that might give her new and even better material to work with, and I still hope that will be the case with her.

Thanks, Marya....

Perfect post for summertime sadness season