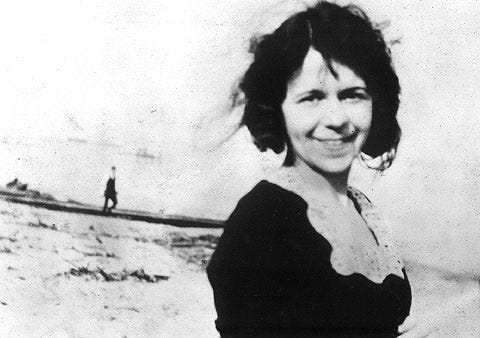

The writer Dawn Powell never got the success and attention she craved and deserved during her lifetime but, as her splendid diary proves, she took her lumps and simply went about her business, putting out a steady stream of novels from the 1930s to the 1950s in spite of poverty and alcoholism and an autistic son who needed constant attention. She is an exemplary figure, an extraordinarily savage and acute satirist who lays her characters bare for liberating laughs and out of respect for the truth. Her books came back into print in the 1990s thanks largely to a loving essay about her by Gore Vidal in the mid-1980s, and Tim Page has heroically kept her name and spirit alive in the 21st century.

Come Back to Sorrento, originally published as The Tenth Moon (1932), was Dawn Powell’s fifth book. It sold less than 3000 copies and, like many of her novels, quickly went out of print. Powell actually thought she was writing an easy crowdpleaser here, but it is easy to see why it did not please the crowd, for she zeroes in on the delusions of her people so thoroughly that there’s something to cringe over on every page.

The two main characters of this book, housewife Connie Benjamin and music teacher Blaine Decker, are so gifted when it comes to self-deception that all we can feel about them, finally, is awe. As Connie reflects (to herself) at one point, “Life is a dragon certain to devour you, but if you keep your eyes shut, you won’t mind so much.”

We first come upon Connie sitting on her porch in Dell River, Ohio, dreaming away, hiding from her two daughters and her inarticulate husband Gus. She truly lives in her own world, and the remarkable thing about Connie is how much she is able to get out of so little. Connie is 35; when she was 19, she had sung for “the great Morini” and he had claimed she had “the throat of an artist!” What might have been a meaningless piece of flattery has become for Connie the triumph of her life (she mentions it to everyone she meets).

But her grandfather wouldn’t pay to train her voice, and the spirited young Connie ran off with a circus performer, a beautiful boy in silver tights who left her pregnant and broke. Gus came to her rescue, brought her to Dell River, and that was that. Connie does what she has to do around the house, but she’s as out of it as can be managed, a pleasant sleepwalker, until Blaine Decker takes the room over Gus’s shop.

Blaine had dreams as well, of a concert career as a pianist, but he wasn’t good enough, and he and Connie immediately strike up an outlandish mutual support system. “Isn’t it better, I’ve often thought,” says Connie, “for me to be here keeping up with my interests in music, keeping my ideals, than to have failed as an opera singer and been trapped into cheap musical comedy work?” Blaine agrees wholeheartedly. He too feels that practicing his art would make him, well, less of an artist.

These two are clearly able to fool themselves about nearly anything without much help, but together they’re unstoppable. Connie begins to think of herself not as a bored provincial wife and mother but as Madame Benjamin, a visiting artist among the plebes. Blaine, whose clothes are ragged and whose weird walk incites ridicule in town, convinces himself that he’s an envied bon vivant who does a little teaching on the side. They aren’t the only ones in Dell River with delusions. Of Mrs. Busch, who takes in washing, Powell writes, “Her casual references to her work made it seem that her long days of laundering were only a gentlewoman’s hobby.”

There are times in Come Back to Sorrento when Powell’s insights into her self-absorbed people are so unrelievedly harsh that we might long for a sensible voice of contrast, or some brief flair of actual communication. But Powell mistrusts words as much as Stendhal did: “You cannot talk about real things, there are no words for genuine despair, there are not even tears, there is only a heavenly numbness for which to pray and upon that gray curtain words may dance as words were intended to do, fans and pretty masks put up to shield the heart,” she writes. In Come Back to Sorrento, Mrs. Murrell, a teacher who works with Blaine, feels the same way: “(she) could not talk about books or poetry lightly, it was like taking out one’s very heart and playing bean-bag with it.”

It’s made clear (at least to a modern reader) that Blaine is a homosexual, and Powell doesn’t overplay her hand in this area, but it’s still surprising that she wrote of this in 1932 in such a matter-of-fact way. Blaine has to send money to his mother, who writes him back nice things like, “I sometimes wonder, Blaine, if I didn’t emphasize the artistic too much in your childhood, encouraging you and perhaps forcing you beyond your real capabilities in music. It was only because you did so poorly in school, dear, and I was glad to find something in which you could excel.” Blaine still carries a torch for his one-time roommate Starr Donnell, who has become a famous novelist.

Powell isn’t afraid to make Blaine unlikable when he puts on airs (Connie’s fuzzy out-of-touchness is funnier, even when she goes too far with it). She makes us see how unbearable Blaine is to everyone but Connie and Mrs. Murrell, but she has a helpless fascination with failure and how people cope with it. Powell paints a gruesome picture of Blaine’s humiliation over his lack of money and shabby clothes, and she clearly identifies with this aspect of his plight. It’s really no wonder that Blaine retreats into fantasy as Connie does. The difference between them is that Connie does have a strong singing voice and is beautiful; what she didn’t have was the nerve to make use of her gifts. Blaine, though, nerve or no, would probably have always been a loser.

Powell spares Connie and Blaine nothing, and her compassion for them is never shown to us directly. There are times when it even feels like she is gloating over their faults as she tears them limb from limb: “They talked of music until the careers they once planned were the careers they actually had had but had given up for the superior joys of simple living.” But in sometimes exaggerating for effect, Powell is getting at a basic truth about many human relationships in which the other person is simply there for comfort and flattery. And why not? Powell seems to ask.

Powell is so cutting because she knows the material she has hit on, about giving up and lying to yourself, is so devastating; the only way to handle it is to go all the way. And in the end, when these two dreamers get smacked in the face by reality, they comfort each other as gently as possible. They aren’t fools anymore to be made fun of; they’re fragile living creatures, deluded, yes, but vivid and hurt and hard to forget.

Happy to hear that, Jan--:)-

Thank you for this reminder of Dawn Powell. I read the volume of her diaries back when it came out, but not her novels (or if I read one I don’t remember), and now I feel I have a lot to look forward to.