In her delightful and witty memoir A View from a Broad (1980), closet bookworm Bette Midler writes of the time she entered a forbidden part of a library in the Hawaiian town she grew up in, where she felt like an outcast, and read Oscar Wilde’s dictum that if you wear a mask you can tell the truth. Something clicked for the young Midler then, and the seed was planted for her stage persona, the magpie Divine Miss M, who was birthed at the Continental Baths of the Ansonia Hotel in Manhattan in 1971.

Over the next 50 years, her Divine Miss M show would grow into one of the all-time great live acts, steeped in the most tawdry and obscure show business legends and routines and presided over by the ghost of Sophie Tucker, “a true vulgarian,” Midler called her proudly, and the “Soph” jokes she would tell that at first began, “I will never forget it” and gradually became, “I will never forget it, you know!”

All show business divas seem to live in Midler and she lets herself become possessed by them in turn: Soph, Mae West, Marlene Dietrich, even a bit of Katharine Hepburn at times, for she has her schoolmarm side. Midler is a Dadaist at heart, at her best when driving her audience to wonder, “What?!” with pleasure, as when she makes a Hawaiian entrance on a half-shell in her first network TV special ‘Ol Red Hair Is Back (1977) and then starts to belt out, “Oklahoma!”

On that special the Divine also sings “La Vie en Rose” against a Klimt painting background, a choice that seems very influenced by Color Me Barbra (1966), Barbra Streisand’s second TV special. Midler and Streisand are very different, but it’s impossible not to compare their careers because they have long occupied such similar positions in show business. Streisand was only briefly an exciting live act, in the early 1960s, and by the time Midler emerged in the 1970s she had stopped performing live. Streisand made it in her early twenties, whereas Midler had to wait until her early thirties before she really came to widespread fame.

Midler did old tunes and camped them as Streisand did in her early act, but Midler is the ultimate in inside baseball show biz and gay references; in her act at the Baths, she refers to herself as Mother, as in, “Your Mother is up here working!” Streisand has always seemed uneasy about her alliance with gay men at the beginning of her career, and she is utterly un-hip. Midler is always ultra-aware of everything about herself and her act and her status; past the early 1970s, Streisand became near-totally unaware of how she was coming across. Midler is so inside that when she enters in King Kong’s hand for her first special The Bette Midler Show (1976) and cries, “Nicky Arnstein!” it will seem perplexing to anyone who doesn’t know or remember that Streisand was briefly considered for the role of the heroine in the 1976 remake of King Kong.

Both are reputed to be “difficult,” though Midler’s long-time writer Bruce Vilanch, as aware as she is, has said that “people say” Midler is difficult, but she isn’t, by his lights; she just needs to work herself into a kind of frenzy to get her new act together and to perform, whereas Streisand is so focused on control that she might never settle on a choice because there are so many. On her short-lived TV sitcom Bette (2000), Midler even gets into Barbra-drag from this period, all sleek white Donna Karan gown and long blonde hair and fingernails poised to command.

Midler did all-out rock numbers in her 1970s act and played a Janis Joplin figure in her official film debut The Rose (1979), whereas Streisand made a very unconvincing rock singer in A Star Is Born (1976) and has no sense of rhythm (Midler could do fairly elaborate dance routines with her back-up singers The Harlettes). When she is really feeling a song, Midler seems overcome by what can only be called the spirit, something that can be found in its purest form in Black churches, whereas Streisand is profoundly un-Black. The Divine Miss M loves to lose control, or simulate that state. As Vilanch also said of the Divine, if you opened Pandora’s Box, she is what you would find at the bottom of it.

Midler’s character in The Rose foolishly comes to grief trying to repair past hurts from her adolescence, and this same urge is eventually what tainted Streisand’s creative drive by the late 1980s and 1990s. Midler had a success on TV in a movie of Gypsy (1993), which Streisand wanted to do as a feature in the 2010s, but she came to this role far too late and got stymied. Streisand is happy to interact with all her comely leading men on screen in her films whereas Midler is like the original star of Gypsy, Ethel Merman, in her total focus on herself; everyone else on stage or on screen to her is another Harlette, there to make her shine, and she’s very aware of that and makes it a show biz joke for her act.

Midler’s discography is sparing compared to Streisand’s large catalogue: 14 or so studio albums and some soundtracks, and she kept to the eclectic choice of songs that Streisand abandoned early. In her initial act at the Continental Baths, she works the crowd and “sells” the songs the way old vaudevillians used to, and the electricity of her style comes across even in the grainy black-and-white footage that remains of this first emergence.

Her early patter is cutting and knowing and sometimes very obscure; she says she was going to work Cherry Grove out on Fire Island but “they couldn’t find room for me in the bushes!” and says that Martha Raye was seen with a large button on her chest that read, “Joan Crawford Is a Heterosexual!” and even I can’t follow the drift of that one. But the queens howl when the Divine announces that Raye was “mugged by the Viet Cong in the Christopher Street tearoom!”

The Divine does dirty blues songs at the Baths and sometimes looks like she’s ready to speak in tongues, and surely she would have a fast wisecrack about that, too. She can be aggressive with her audience, and it isn’t always a put-on; she knows she has to be a kind of lion tamer with the crowd. “Get that blood circulating, your Mother is up here working!” she demands, having taken on this gay argot for herself as one of the tribe, one of our great queens, and maybe the funniest of them all.

“My mother doesn’t speak to me anymore!” the Divine cries at the Baths, yet Midler has said that she appeared in her first movie, a ghastly independent production made in Detroit in 1971 variously called The Thorn and The Divine Mr. J., because she had to pay a long distance phone bill to her mother in Hawaii, and the eight people who have seen this usually-suppressed picture can only commend her mother love. It is a wonder that no one told her to put a little make-up on for The Thorn or do her hair for this thing, which sometimes turns up on YouTube, though Midler worked hard to have it banned after her first success. It’s a little like Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) in its use of limited footage of Midler in the way that a short amount of film of Bela Lugosi is repeated in the Wood movie.

But Midler soon appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, who told her she was going to be a big star and also that she tended to dress “like a stolen car.” Midler has always been at her very best on talk shows because her restless mind is always in overdrive and she is instinctively negative in an excitingly unpredictable way, whereas most people in show business are positive in a phony way.

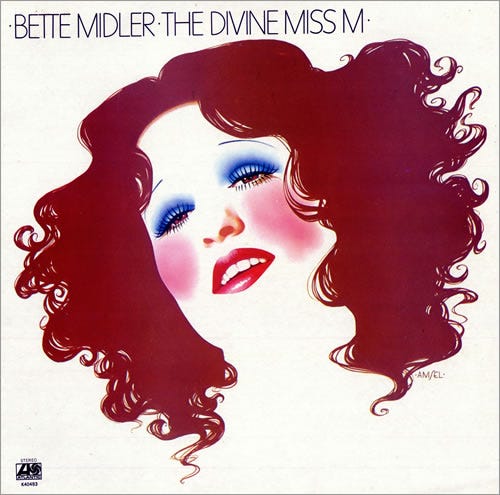

Midler released her first albums, with their upbeat covers of 1940s tunes like “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” and “In the Mood,” and she worked up her act, which was first captured in full for HBO in 1976. The original Harlettes were dressed and comported themselves like streetwalkers; as time went on the newer Harlettes got far slicker and less threatening. Midler makes an entrance here in a hospital bed and flashes her megawatt Star Smile before working the stage like Tina Turner and Mick Jagger combined, and she is a Lucy redhead now, too, a mash-up of superstars or all superstars combined for one smash performance.

There is something of the joyfully uninhibited child entertaining the grown-ups about Midler in this period sometimes, yet the word “motherfucker” comes naturally to her, and she comes out with lines like, “I donated my tits…to Cher!” Some of the things she said in this 1970s act would never fly now, and they were dicey even then, but her motto was, “Fuck ‘em if they can’t take a joke!” The Divine was also pledged to grudge-holding and spite, and the motto for Midler’s eventual film production company was “We Hold a Grudge.”

For all her super-human energy, sometimes the Divine is funniest when she is doing the least, as in her “impressions,” which are one of the lowest forms for a comic. She’ll “do” Arlene Francis on What’s My Line? so briefly and sketchily that what’s funny is how pointless it is, yet at the same time Midler has a queer love of rescuing the most obscure figures even if for a moment. When an audience member calls out for her to “do” Shelley Winters in The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Midler delightedly gets a stool and does a few panicked swimming strokes with face to match, but only briefly, and even this early she confides to her audience that she gets physically tired up there on stage. The Divine is often a Tired Mother, and that’s part of her humor.

For slow-minded people, or people who like things to be stately and wholesome and so forth, the Divine is their worst nightmare, but for those who delight most in fast badinage, the Divine is a dream, and part of her spirit is a far-reaching vocabulary that seems borrowed sometimes from Bing Crosby and a range of reference that isn’t afraid to be highbrow. “I want the show to be a vindication of Tolstoy’s innocence!” the Divine announces on her network special ‘Ol Red Hair Is Back, and she gets in a whopper of a double entendre when she refers to “you box watchers out there.” Her audience here is far colder than usual, and at the end Midler even tries to be like Loretta Young in sweetly hoping people will tune in for her again, but at least her sponsor is the American Ladies Garment Workers Union.

The Rose was and still is her biggie as a film performance, set in 1969, which was already deep period by 1979, lensed in garish colors by Vilmos Zsigmond, and all but undirected by Mark Rydell, who also absently presided over a later tour-de-force for her, For the Boys (1991). Midler is so good in The Rose partly because the character she is playing is so exhausted that her performing defenses and masks have to be down, and tiredness as a concept has always stimulated her best work. She moves like a jungle cat on stage and goes all out with the sexuality of this woman, who is a 100% innocent and feels the need to apologize almost instantly after throwing a diva fit of some kind. The Divine Miss M is ultra-confident, whereas The Rose is not, but in Rose’s concert performances Midler shows us the greatness that is being lost as this woman gets extinguished by her demons.

In one of the most upsetting scenes in The Rose, Harry Dean Stanton’s country star tells Rose off because by his lights she’s a vulgar tramp, and he doesn’t bother to see the quivering childlike innocence that is standing right in front of him as her huge hopeful smile falls away from her face; she descends into a panic when she realizes that he has insulted her in no uncertain terms and no one in her entourage has come to her defense. During the last 20 minutes of The Rose, Midler is out on the edge as her character nears death, outraged and stunned, letting out a howl as she goes down the drain, and she was nominated for an Oscar but lost to Sally Field in Norma Rae, which Midler made into a grudge-holding comic routine for the rest of her career.

Midler’s Rose kills herself emotionally on every number she does, and of course she can’t keep doing this to order all the time, which was the problem that so many singers had from Billie Holiday to Judy Garland and on to the rock stars like Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse. It is an open question whether Midler herself ever came this close to the edge when she had a breakdown in the early 1980s after the troubled production of Jinxed (1982), but there seems to have been a harder core with her that helped her get over the bad times. She was hilarious at the 1981 Oscars dishing the nominated songs, and her low-selling comedy album Mud Will Be Flung Tonight! (1985) is a scream. On Bruce Springsteen she says, “Hell, I remember when his arms were as skinny as his chord changes!” and of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” she cracks, “Touched for the very first time…today!”

Midler was married by that point to Martin von Haselberg, and it was a marriage that lasted. She re-emerged as a very funny part of the ensemble in Paul Mazursky’s comedy Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), probably the best movie Midler was ever in, a controlled farce where she gets to play a rich wife who longs for some sexual fulfillment and at one point sings “You Belong to Me.” After that Midler headlined a series of films for Touchstone, a branch of the Disney company, and these years from age 40 to 50 were prime years for her commercially, if not always creatively.

With “The Wind Beneath My Wings,” a song she sang for the tearjerker Beaches (1988), the Divine stepped aside and allowed her corny alter egos Vickie Eydie and Delores Delago to cut a different kind of cheese all the way to the bank, and surely Midler’s always-expressive hand gestures were better suited to just about anything else in her repertoire. But only the most priggishly anti-establishment would be too outraged about Mother getting such a big hit with what the Divine termed an “inspirational ballad,” like her other mega-hit “From a Distance,” an early 1990s staple on the radio meant to make you feel vaguely comforted by the idea of giving peace a chance.

Her Mama Rose on TV in Gypsy (1993) was another of Midler’s innocents. It is the innocence of her stage mother Rose that makes her cunning with her daughters even more disturbing, and Midler’s rendition of “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” is everything it needs to be: exciting, even a little attractive, yet scary. Midler shows here that a lot of us would be capable of Rose’s mistaken stubbornness, and as a noted grudge-holder maybe she understands the tragic side of this.

Midler had a hit with Goldie Hawn and Diane Keaton in The First Wives Club (1996) and belted out “You Don’t Own Me” with them at the end in a way that couldn’t be more seductive or inviting; this is pure star power in triplicate, ecstatic being and becoming, and whatever the merits of the film, this last number is endlessly re-watchable as a tonic on YouTube.

Midler’s live act stayed knowing and pleasure-giving as she conquered Las Vegas, stuck to short blonde hair and sleek figure in black, and crowed, “I look good!” while extolling the merits of “pretty legs and great big knockers” and admitting how she had been “compromised, Walt Disney-ized!” The rock songs were gone now, but the humor was still up-to-date and stiletto-like; if she has it, she flaunts it, and fuck you! And though Midler is at heart a crowd-pleaser, that “fuck you!” is only partly in jest. Though she brought out “those inspirational ballads you love me for” for the squares, she was still the Divine, basically unchanged, a source of such bawdy suggestiveness and such blissful speed of thought. “30 years ago my audience was on drugs,” she says, “now they’re on medication!”

The central joke in Midler’s Vegas act was that she kept trying to keep the show from getting too dirty for the squares, and of course she enjoyed the “failure” of this attempt. And she was still “working the balls,” the actual balls on the ends of strings that she had been spinning since her early days in Hawaii when the young Midler decided to get herself some masks to wear. “They’ll tell you, I’m the biggest Mother they ever worked for!” she cries of the new Harlettes, who are often augmented by Vegas showgirls. She shared a theater with Cher: “Does it get any gayer?” the Divine asks. At later points she might ask, “Did I sing the ballad yet? Was it wonderful?”

Through all the years in her live act Midler disdains the front row and gives love and more cleavage to the balcony, and her early shows cost six bucks and then ten bucks, but bigger bucks were to be had, until when she played in Hello, Dolly! on Broadway in 2017 the price of a top ticket was what most people pay for a month’s rent. But, like only the greatest stars, there are things that only Midler or one of her alter egos can do. Bootleg footage of her selling the song “So Long, Dearie” in that show is just as electrifying as her early act at the Baths, and the scene where her Dolly consumed a table full of food with obscenely sensual relish is a highpoint in truly out-there comic schtick, all carefully prepared for, utterly technical, and pure Bette Midler in that it gets us to wonder, “Just what is it that I’m watching here?”

Compared to other celebrities, we know little about the real person behind the mask; it is clear that there are areas of her life that are private, and she is only an exhibitionist in character on stage. Midler herself has been a kind of alter ego for Bruce Vilanch, and both of them have a Muppet-like quality that sometimes belies or excuses their sharp tongues. He is the one who gave her the impetus for the Soph character, who was supposed to be around age 60 when they started with her and has since reached the age of 93 while still getting up to her old antics at nursing homes.

Midler sometimes goes up to the edge of what might be deemed acceptable as discourse because she feels the need to question everything, or poke and prod at it, and this can sometimes be, at the very least, politically inconvenient. She is maybe the last of a kind of old school trouper, yet she is modernist in the way she is so alive to the most arcane show business lore and can drop a reference that will surprise or bewilder her audience.

The Talent Fairy dropped a ton of fairy dust on Midler, so much that she had to parcel it out to different personas. What is left in considering her achievement, finally, but awe at the energy that went into creating this character the Divine, this act that has given so many people the deepest, most consoling pleasure? But surely the Divine herself would finally tell me to shut up just as she’ll tell unruly audience members a motto from Belle Barth, “Shut your hole, honey, mine’s making money!”

PS: Here’s precious bootleg footage of Midler selling “So Long, Dearie” in Hello, Dolly! on Broadway in 2017. Look at the beautifully worked-out camp hand gestures (like Lucille Ball, she leaves nothing to chance), the Mae West-shimmying, the seizing of that stage. No one living can sell a song like Mother M.

Very happy you enjoyed, Bernard...I will never forget it, you know.

I could not say it better than Bernard Welt, what a superb article, and all accurate! I have been a Bette fan since I first saw her as a teenager (me, not Bette) on Johnny Carson singing Leader of the Pack and then Hello In There, show on me over. I have seen her live every show I could from 1973 to Divine Intervention and ALL in between. The best live performer I have ever seen, I feel so fortunate to have followed her career as she has brought me such joy. Thank you for putting it all in writing Mr. Dan Callahan.