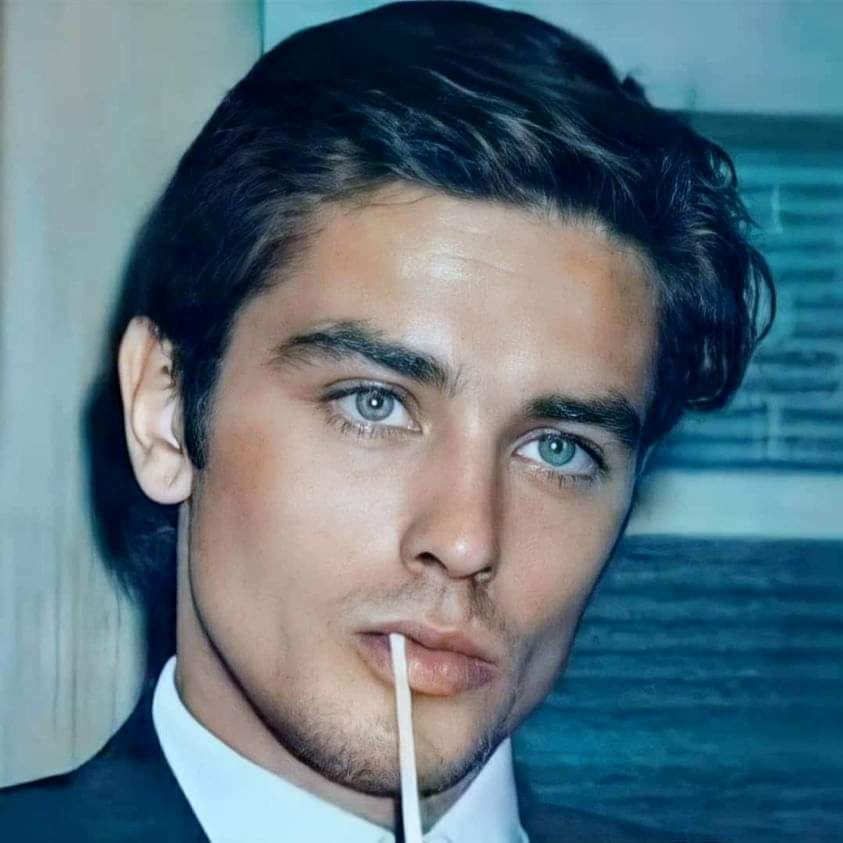

Certainly if it were to be said that Alain Delon was the most physically beautiful man to ever star in movies, you wouldn’t get too many arguments. Who might compete with him? Brad Pitt? Buster Crabbe? Guy Madison? All three of those choices are blonds, and all three have a sweet quality that the cat-like Delon does not. (And when I say “cat-like,” I don’t mean a house cat. Didn’t Delon always seem like a sleek jungle cat who was considering not if he would tear you to pieces, but when?) Gary Cooper or Paul Newman might also take that title, but they were men who seemed eaten up by anxiety, tormented by thoughts of lost nobility that might be regained. Delon had no such doubts. His most characteristic role, Ripley in Purple Noon (1960), is a narcissistic sociopath whose chief love object is himself.

Delon often said that Romy Schneider was the love of his life, and he even kept her ashes after her death in 1982. But on screen, did he ever have an encounter with a woman that matched the rapture of the moment in Purple Noon where he basically makes out with himself in a mirror? When you look like Alain Delon, you inhabit a special category, and what’s notable is just how menacing he made that “most beautiful of them all” category seem. During his headiest days as a movie star, and even long afterward, Delon would often refer to himself in the third person, as in, “But of course Alain Delon would do that,” and so he was hyper-conscious of his image as a pretty-boy tough guy in a trench coat who walked through life in a kind of trance, as he does in perhaps his most famous movie, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967).

As a youth growing up in France, Delon was noted for his bad attitude and rebellious nature, and his extreme beauty is evident already in a short film he made at age 14 called Le Rapt (1949). He got expelled from school, and he also got expelled from the navy during his military service and spent his 20th birthday in a cell for theft of a jeep (he had earlier been reprimanded for stealing equipment). This strain of the criminal in Delon would lead him to gravitate toward underworld figures back in France, but he got a small part in a movie while living with the actress Brigitte Auber, and a key piece of advice from his director Yves Allégret: “Listen to me, Alain. Speak as you speak to me. Look at me as you look at me. Listen as you listen to me. Don’t play, live.” Delon was set from then on. “It changed everything,” he said. “If Yves Allégret hadn’t told me that, I wouldn’t have had this career.”

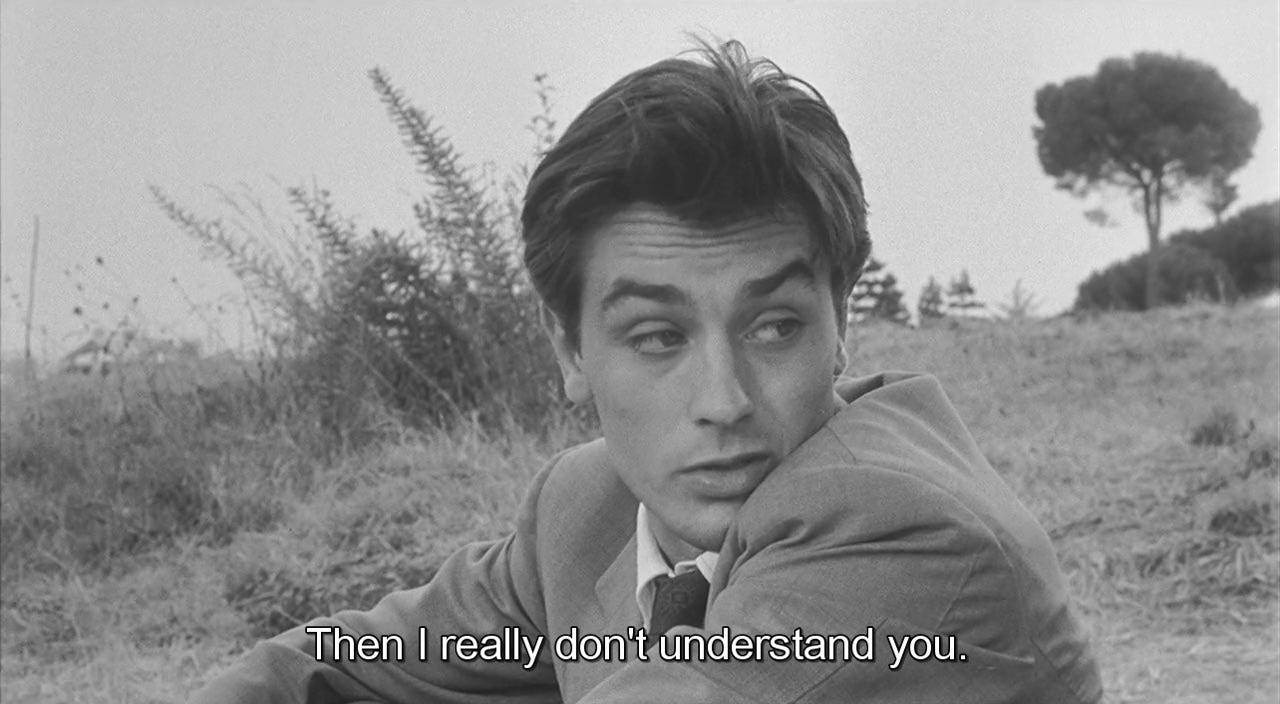

While making the movie Christine (1958), he fell madly in love with Romy Schneider, who herself had very cat-like qualities, but she had a warmth that he was drawn to. He had his first large success in 1960, when he made Purple Noon and Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers, so that he was a self-loving killer in thrall to a Technicolor high life in the first and an angelic victim in black and white in the second and adored by Visconti’s camera, which labored to find something sweet and human in him.

Better still, Delon was cast as a shark-like stockbroker in Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse (1962), circling an ennui-plagued Monica Vitti like a man who would like to have sympathy for her if such sympathy were available to him, which links his usual sociopathy to a ruthless capitalist point of view. An attempt at Hollywood moviemaking did not work out, and he came into his own back in France in a series of gangster films, the best of which were a series for Jean-Pierre Melville starting with Le Samouraï, where he is at his most alien-like and abstract.

In 1969, Delon’s friend and bodyguard Stevan Marković was found murdered, and this led to many unsavory rumors about Delon’s ties to organized crime. “If I get killed, it’s 100% the fault of Alain Delon and his godfather François Marcantoni,” read a note by Marković to his brother, and there was talk about sex parties and clandestine photos of political higher-ups, and all this only added to Delon’s very dangerous allure on screen.

He boldly admitted to bisexuality in a TV interview from that same year, and his appearances in gangster films accelerated, but he was at his best again for Joseph Losey in Mr. Klein (1976), a film in which his art dealer character attempts to exploit Nazi persecution of Jewish people for profit but becomes ensnared in that persecution himself, and this showed that Delon could be at his middle-period finest as a cornered animal desperately trying to escape being trapped.

In 1978, Delon was at his very best as the silent object of desire in a film of the Jean Cocteau playlet Le bel indifférent, observing a woman who is consumingly in love with him with a stirring mixture of both warning and pity, a signal that Delon himself did have something human in him somewhere, deep down, if he cared to show it, the humanity steeped in romanticism that insisted on keeping Romy Schneider’s ashes. He was still beautiful as the Baron de Charlus in Swann in Love (1984), and amid more commercial films he was still open to challenging himself, as he did for Jean-Luc Godard in the very un-commercial Nouvelle Vague (1990).

His later years were messy and marked by increasing right-wing comments and family squabbles, and there was even talk by Delon of euthanasia as he entered his late eighties. All of this will fade. What matters about Delon is that face of his up on the screen in his best movies, and the way that even in the least of his movies he moves like an animal in a cage that might spring at you and claw you to death at any moment.

Imagine being 13 or 14 years old and seeing the face of Alain Delon staring back at you. Imagine the feeling of power that might arise from that, the insolence, the feeling of protection and being set apart. Then imagine the wolves who might make a play for you on the way up, and the men who will definitely resent such a face. (Remember that famous photo of Mick Jagger stewing in impotent jealousy as Delon speaks to Jagger’s girlfriend Marianne Faithfull, and Jagger was one of the sexiest and most charismatic men on earth then.)

Everything about Delon’s beauty had a sinister quality made for neo-noir films, but maybe, like his character in Le Samouraï, he sometimes wanted to know what it would be like to be human, to care. Maybe that face was also a prison, and as the prison crumbled during the aging process Delon’s uglier nature came through. Most of us want to ascribe good character and motives to extremely beautiful people, but Delon was the most beautiful male in movies of them all, and everything about him said, “Not so fast, you want me to be an angel, but….”

PS: I had planned on running another piece today, but a figure like Delon demands to be dealt with. If you've been enjoying these pieces I do every Sunday, please consider becoming a free subscriber, or even a paid subscriber in order to tip the piano player or put a single in his jockstrap, etc.

Thanks very much, Jay--

The more I read about Delon, the more unnerved I get. It's a disturbing thought that someone gets away with some really awful crimes purely because they look angelic. It doesn't say much for us as a species, does it.

I mean, yes, he probably had his gangster bestie kill Markovic after Natalie showed him a sex tape the two made. Maybe that was her way of getting back at a guy who seemed willing to screw anything that moved. She herself was questioned about the murder. She developed a heroin addiction around the same time. The sentimental Delon was, of course, there to make sure she went into treatment. And let the papers know that he'd done so. Markovic was the second Delon 'bodyguard' to die in strange circumstances.

Another bit of Delon roadkill was Nico. He was screwing her while still ostensibly with Romy, and wouldn't acknowledge their child Ari. According to Marianne Faithful, Delon's treatment sent Nico off the rails, she struggled financially. Died an addict at 50. While she was addicted to heroin, she gave Ari to Delon's mother Edith, who had no doubts about his paternity. Marianne called Delon a pig. Edith said he was evil. Ari had a tragic life. He was never acknowledged, he became an addict. and he died alone, confined to a wheelchair. His decomposed body was found later.

Then there's the original sin. Romy. However poetic Delon liked to wax after the fact, reading posthumous love letters on live tv, he left her after 5 years with a bunch of roses and a note "I'm in Mexico with Nathalie. All the best, Alain." Apparently she tried to commit suicide for the second time after this. The first time was allegedly when she found him in bed with a man. Romy was addicted to tranquilizers and died at 43. But he kept her ashes. How sweet.

His commanding officer in Indochine labelled him "a sadist who liked killing and a sexual pervert." I mean, you can analyse his disjointed childhood during wartime, being shuffled between divorced parents with new families, and fostered by an abusive man. The truancy, expulsions, thefts etc. Maybe some degree of sociopathy was inevitable.

But he loved animals, you cry! How bad could he be? Maybe he preferred them because dogs make no demands, they adore unquestioningly, and they're easier to control. He wanted his last dog, Loubo, to be killed after he died so they could go together. Loubo, as I understand it, was not euthanized per request, and is still alive and kicking.

One of the few who survived close contact with Delon. Superficially beautiful he might have been, but there's a helluva lot of ugly to plumb. It's a creepy combination.