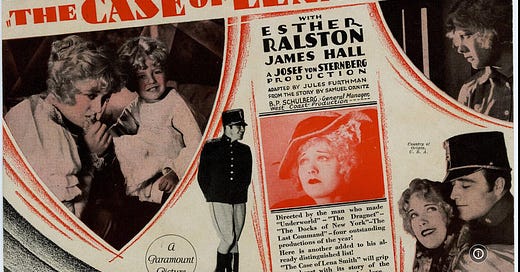

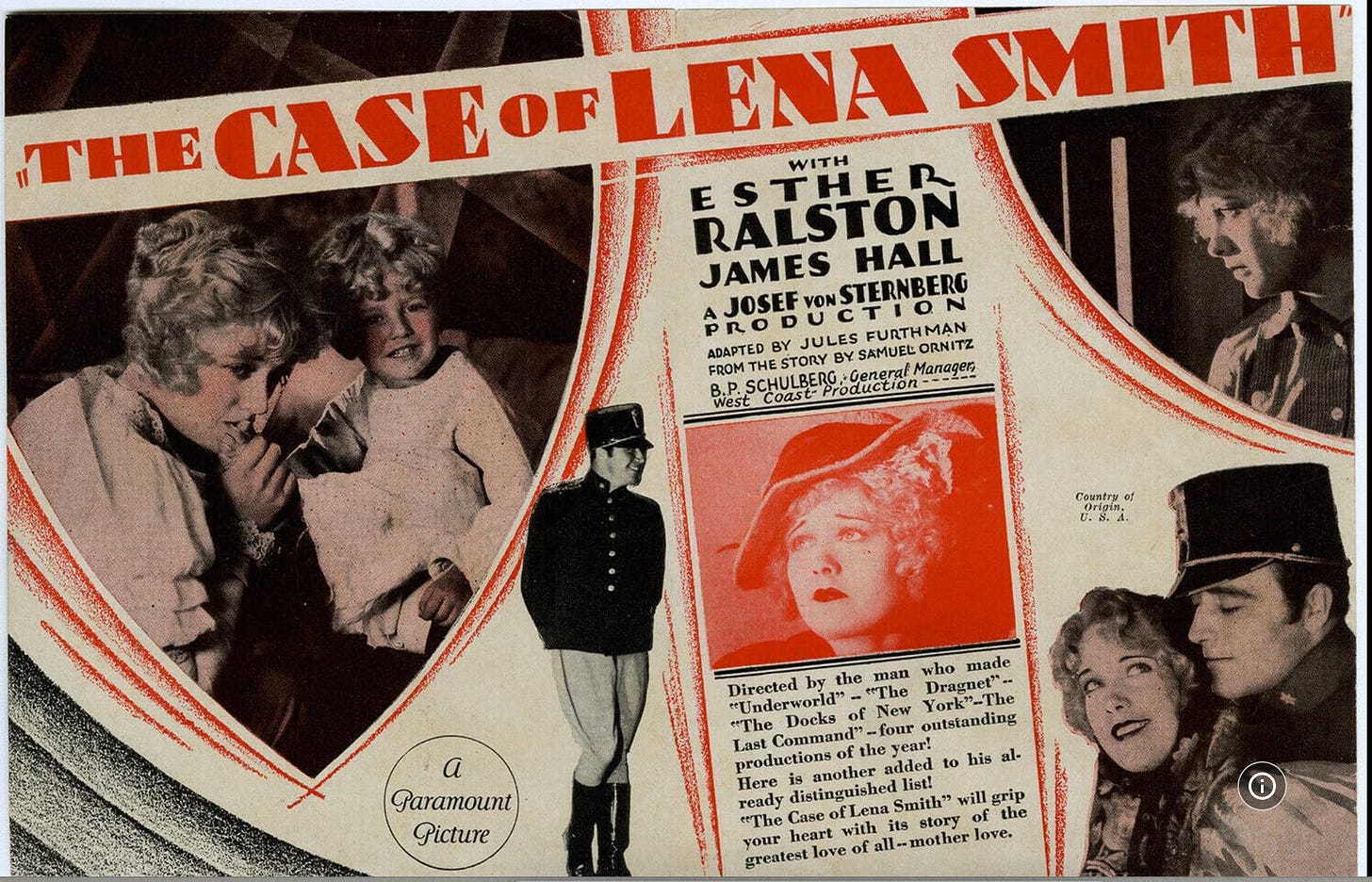

I recently discovered a fragment of a lost Josef von Sternberg silent movie called The Case of Lena Smith (1929), which was made the same year as his first talkies: the gangster picture Thunderbolt and The Blue Angel, which began his storied creative partnership with Marlene Dietrich. The plot of the film sounds a bit like the later Sternberg-Dietrich movie Blonde Venus (1932) in its emphasis on mother love, and its star is Esther Ralston, whose starring career was ended, she said, when she would not sleep with MGM head Louis B. Mayer.

The Case of Lena Smith is not the only lost Sternberg movie; there is also The Drag Net (1928), a gangster picture starring George Bancroft, and an MGM movie called The Exquisite Sinner (1926) that was scrapped and re-shot. Sternberg also made a film for Charlie Chaplin called A Woman of the Sea (1926) that was destroyed because Chaplin was unhappy with the performance of his long-time leading lady Edna Purviance

The director and cinephile Curtis Harrington managed to see The Case of Lena Smith before it was destroyed by Paramount in the late 1940s for tax purposes, and he spoke highly of it in a 1949 issue of Sight & Sound magazine: “The Case of Lena Smith may be regarded as von Sternberg’s most successful attempt at combining a story of meaning and purpose with his very original style.”

It was only in 2003 that the Japanese film historian Komatsu Hiroshi discovered a fragment of this lost movie that runs around four minutes. This recovered sequence comes towards the beginning of The Case of Lena Smith, after a prologue in which we would have seen Ralston’s Lena as an older woman at the start of World War I. In a flashback to her youth, circa 1894, Lena spurns her fiancée and goes with female friends to find work and pleasure in Vienna, a city dear to Sternberg’s heart. In the fragment, we first see a bucolic image and then one of Sternberg’s beloved dissolves, this time to a flowery-sarcastic title card. The tone of a Sternberg movie is often difficult to pin down because he was always sneering at romance yet he was the ultimate romantic himself.

We see figures distorted in a funhouse mirror, which is reminiscent of Sternberg’s pyrotechnical wild party montage in Underworld (1927), his hit gangster picture. And then there is a startling shot of a woman perched on a stand with no lower body visible; is this a trick visual effect? Or is she actually missing her lower body? In his 1965 memoir, during a near-page-filling sentence about the Prater of his youth, Sternberg mentions “women who were sawed in half and apparently spent the rest of their lives truncated” and how this impression was passed on to The Case of Lena Smith.

The fairground seems filled with sleazy male officers always tugging at their mustaches, and we get our first sight of Ralston’s blonde Lena looking for one of her friends, who has taken up with a soldier. Lena’s face takes on an “I thought so” expression, and we next see a magician who makes a woman levitate for a gathered crowd; he tips his hat after this feat.

The atmosphere is libidinal, and Sternberg is conjuring a carnival world where desires can be fulfilled and distortions might have their own kind of beauty. Sternberg noted in his memoir that Ralston was a player who accepted all of his direction and was “flattered” by the attention, though he reserved a barb for her husband, who sold him “valueless shares in a gold mine while I was converting his wife into something more valuable than gold.”

A white-gloved officer (James Hall) behind Lena pricks a balloon to get her attention, and he doesn’t need a mustache to stroke to look on the make. He gives her a new balloon, and she shifts her body as if to say, “There was nothing wrong with my old balloon, jerk!” The magician picks Lena out in the crowd and wants to demonstrate his “powers” on her, and she runs away, but her suitor goes after her, and here the fragment ends.

The synopsis of the rest of the film has it that Lena gets pregnant by this wealthy balloon pricker of a man and marries him in secret, and he arranges to have her work as a servant in his family home. He gambles and philanders, and her son is taken from her after Lena is seen with him in the Prater, the place where she first met his scapegrace father. Lena winds up in prison, where she gets whipped by a cruel matron, but she escapes, rescues her son, and takes him to the country from whence she came. The epilogue in 1914 would have shown that the older Lena is angry about the war and thinks that her son will not return from it.

I’ve watched this four-minute fragment of The Case of Lena Smith several times now. If given a choice, most cinephiles would select F.W. Murnau’s 4 Devils (1928) as the lost silent film they would most like to see, and I would choose that, too. But I now think my second choice would be The Case of Lena Smith so as to observe Sternberg’s visual style in full flower and the performance of the neglected Ralston in the lead.

The surviving fragment of The Case of Lena Smith is viewable below:

Thanks for the opportunity to take a look. Ralston looks pretty hearty and healthy here as opposed to Dietrich's neurasthenic aura in his later Paramount's.