The movies that Zalman King made in the late 1980s and 1990s, often in collaboration with his wife Patricia Louisianna Knop, were sneered at by critics because in America it has always been fashionable to mock sex and sexual exploration on screen, particularly if, as was the case in the work of King and Knop, female sexual exploration was the driving force behind it; critics often called their films superficial, but it is their reactions that read as superficial now. I loved their movies as a teenager, and they made a deep impression on me, so much so that, when I recently watched them again, it occurred to me that what I wanted as a young person, and even what I still long for now, was based on what King and Knop had offered me.

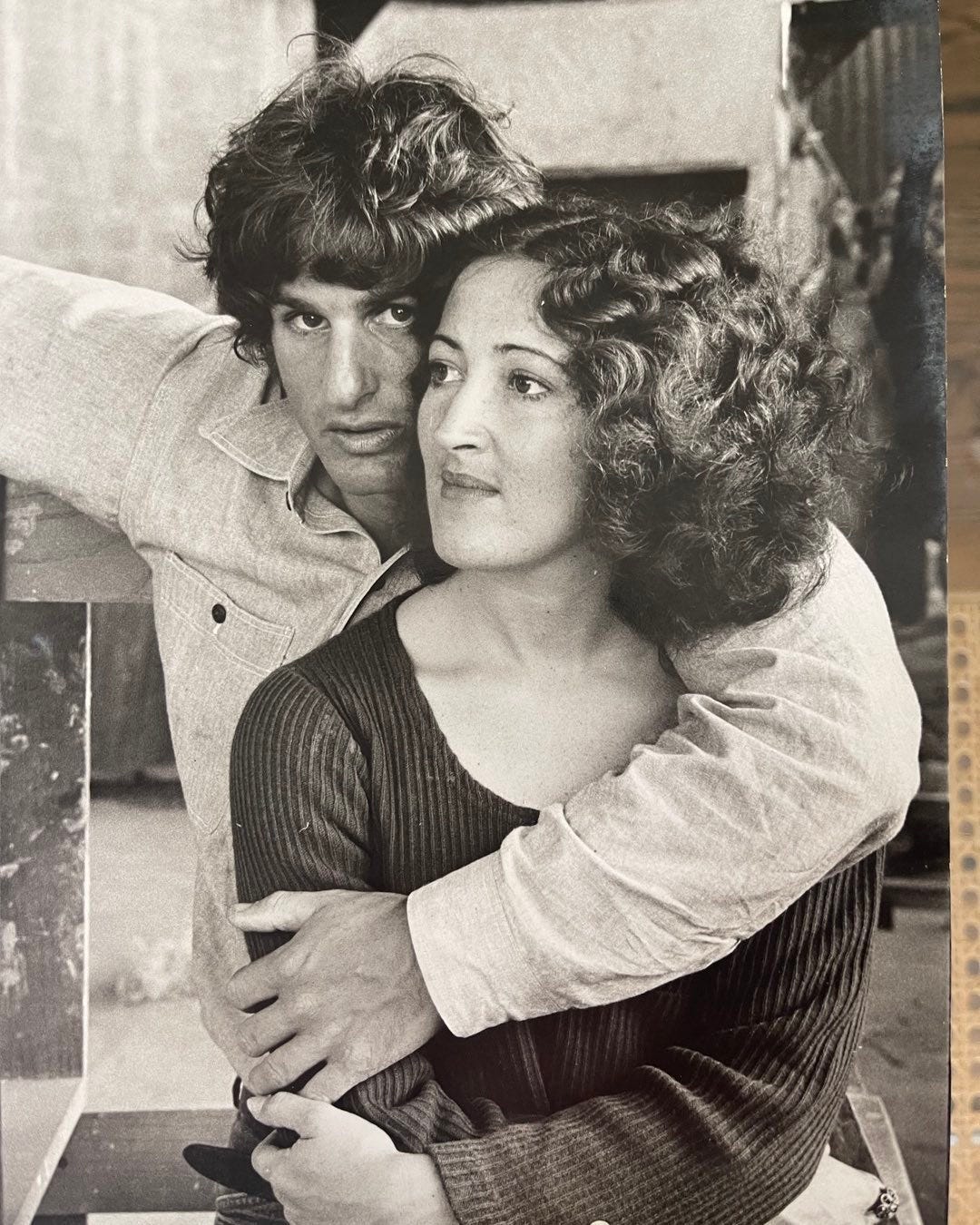

The romance of their work was based around the actual romance of their marriage. King was born Zalman Lefkowitz, and he came from a privileged background, while Knop grew up with very little money. They met when they were very young on a boat trip where Knop had been hired as a deckhand and King as a diver, and when she looked at him for the first time emerging from the sea she thought, “That’s the most beautiful man I have ever seen” and resolved to marry him. Crucially, their marriage, which lasted from 1965 to King’s death in 2012, was based on female desire, on that moment when Knop saw King and fell in love.

King worked as an actor in the 1960s and ‘70s, and Knop worked as a screenwriter; she wrote Lady Oscar (1979) for Jacques Demy, one of the most romantic of all great directors, and a gritty vehicle for Ellen Burstyn called Silence of the North (1981). It was in 1986 that Knop and King first collaborated on a film script, 9 ½ Weeks for director Adrian Lyne, a movie in which a woman (Kim Basinger) is tempted by a male seducer (Mickey Rourke) into sex games involving blindfolds and food. That movie feels much colder than their later work because Lyne gives it a distant visual sheen, whereas King and Knop were pledged to warmth and sincerity.

King alone wrote and directed his first feature, Two Moon Junction (1988), which inaugurated his softcore universe. Though he hated the word softcore, it describes King’s gauzy and gentle style perfectly; he likes scenes to go by so slow that they often have a trancelike quality, and he sets his characters amidst décor in a very elaborate way, as if he is cocooning both them and his audience, blindfolding all of us and leading us into his world of pleasure.

This was a period when you could do an erotic film like this as an up-and-comer (female lead Sherilyn Fenn) or a character actor (Louise Fletcher, Juanita Moore, Burl Ives) without too much trepidation. Fenn’s Southern belle heroine April is set to be married to a good-looking and wealthy man (Martin Hewitt), but she is stirred by a carny worker named Perry (Richard Tyson), and she is a voyeur, staring at naked men through a peephole in a shower stall and then communing with her own horniness in an indelible close-up that looks like a Man Ray photo with her eyes closed and water droplets on her face. When April sleeps with the brazen Perry, she weeps, and at the end of the film she weeps again after opening herself up to the pleasure he gives her. Perry is a classic example of one limitation of King’s work, which is tied to its time period: unflattering long and/or floppy hair on the male sex objects.

This was also a period when AIDs was making everyone fearful of sex, and King tackles this head-on in Two Moon Junction with the introduction of a character named Patti Jean, played by the extremely likable and charismatic television star Kristy McNichol, who was a lesbian and closeted at that time. Forthright Patti Jean asks Fenn’s April of Perry, “Did he make you take an AIDs test before he fucked you?”

King films are all about seduction, and we see brash Patti Jean slowly seducing April, rouging her own nipples and dressing April up and then saying, “It’s at moments like this I can see why guys like women so much.” Out at a bar, Patti Jean insists that April dance with her, and they go out on the floor to move together in silhouette as excluded but intrigued and aroused men look on. This is all a lot for 1988, especially for McNichol, who is bravely putting some of her cards on the table here. Yes, they are in darkness, and yes, we never see them kiss or sleep together, but the possibility is there.

King collaborated with Knop again for Wild Orchid (1989), a Rio de Janeiro erotic fantasia headlined by Mickey Rourke and Carrié Otis, a model whose delivery of dialogue is very stilted, which was an opening to some of the worst reviews they ever got. But there is a tantalizing scene where sharkish businesswoman Jacqueline Bisset tosses her hotel room key down to one of the most gorgeous men who ever lived, Jens Peter, and gets him to take his pants off for her. “Ask him if he understands what tremendous pleasure women get looking at naked men,” Bisset orders Otis, another radical moment spoiled when Rourke enters and jealously disrupts whatever was about to happen.

In the Wild Orchid sequel, again written and directed by King alone, Warhol sex god Joe Dallesandro is a predatory man who seeks the virginity of the heroine Blue (Nina Siemaszko): “You might not like lookin’ at me, but I love lookin’ at you,” he tells her, quite a line for one of the all-time great male pin-ups. Blue becomes a prostitute and works in a bordello where several of the girls talk of enjoying what they do, and they also enjoy the voyeurism of watching clients with other girls through peepholes. King had a fascination with prostitution that comes out in both Wild Orchid movies, but he retreats from any bold viewpoint on it and has his heroines go back to wanting love from one man. There’s also a fetishization of virginity in these movies that feels very conservative early 1990s.

But then King and Knop found a far more attractive and seductive male figurehead for their work in David Duchovny, who was the lead in their feature Red Shoe Diaries (1992) and hosted the resulting series for Showtime, a softcore institution that ran from 1992 to 1997 for 66 episodes (not 69, alas). It is in the Red Shoe feature and the series that Knop really seems to have made her own point of view felt, and of course it is hard not to wonder about Knop and King as a couple and what their marriage was like.

“Well, my wife is a phenomenal writer and she’s also a sculptor and she’s really accomplished and just adorable,” King said in an interview with Jump Cut in 2011. “Patricia has a very humane point of view and she’s the last person you would expect to write eroticism. She’s very attractive and sexy to me, but she’s so non-erotic and so the last person on the planet that would write eroticism… I don’t think Pat thinks about eroticism. I think she thinks more along the lines of ‘this is a really good story and this is how it should be told’…It’s weird because we live a very—well, I can’t say we live a normal life, because we don’t—but eroticism is not a prime thing in the way that we live. I mean, we’re not swingers. It’s more about romance; I think we’re very romantically inclined… Pat’s worldly and I think that her worldliness and sophistication is very helpful to me.”

It seems like King was the one who had the interest in softcore erotic cinema while Knop went along for this ride because he was the love of her life. He had a liking for “trash” and “camp” which comes across in the way he fondly speaks about the films he made as an actor in the 1970s, whereas Knop had a loftier point of view, but where their sensibilities met was in their love of romance and their belief in romantic connection, which they had experienced in life.

King wondered what it would be like to be a seducer of women, the good and the bad side of this, and his work allowed him to explore those fantasies. “I explore it because it interests me,” King said in his interview with Jump Cut. “I think I would personally have the ability to be like that. I’ve been married for a very long time and it’s the greatest thing that ever happened to me, but do I have Mickey Rourke in me? Absolutely. And do I want to be Mickey Rourke? No.”

But David Duchovny was far preferable to Rourke in this regard, and it feels like Knop must have felt that, too, since Duchovny’s looks are very close to King’s. “He was way more concerned with the color of the drapes than showing any T&A,” said Duchovny after King’s death in 2012, calling him an eccentric enthusiast who was able to inspire his casts and crews and make them feel they were creating something beautiful together. Duchovny was smart, amused, witty, and filthy in a good way, whereas Rourke just made attempts at such qualities. Duchovny was also a sexy Jewish guy and something of an intellectual, and so he is like the embodiment of the idea that Knop-King seemed to have of themselves as a couple.

In the Red Shoe Diaries feature, Duchovny’s Jake Winters is first seen at the funeral of his fiancée Alex (Brigitte Bako), who committed suicide. He finds her diary and learns that she had an affair with a blue-collar guy named Tom (Billy Wirth), who is like a darker version of Jake, a seducer who screws like a jackhammer. Alex’s need for this is tied to her propensity for self-destruction, and this is so carefully written that it feels like Knop has had a firm hand in it. The blue-collar male lover a woman can’t get rid of is the fresh 1990s theme here, a variation on the female mistress that the man can’t get rid of of old.

At the end of the Red Shoe feature, Jake confronts Tom, and it feels now like Jake could possibly screw Tom out of his need for vengeance, for King-Knop seem open to such things, yet the market in 1992, of course, was not. But in their best collaboration Delta of Venus (1995), a film based on Anaïs Nin’s erotica classic, they reached an apotheosis of everything they wanted to do together creatively, and this is partly because of the freedom they found in the bohemian atmosphere of the setting in circa-1940 Paris.

Black characters had been on the periphery of all the King films so far as a kind of example of greater emotional freedom. A Jamaican cabbie (John Toles-Bey) helps seal the deal for Steven Bauer with Joan Severance at the beginning of the first episode of Red Shoe Diaries called “Safe Sex,” and it is clear that he desires Severance himself, but that possibility is blocked. In Delta of Venus, there is finally a sex scene involving a Black character, a proud and beautiful man (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje) in a light grey suit who caresses a redheaded streetwalker (Markéta Hrubesová) as close to her body as possible without actually touching her, a visual metaphor for the forbidden nature of their coupling that falls away when he disrobes and takes her with force and pleasure.

There is a very brief shot of two men kissing during Carnivale in Wild Orchid, but in Delta of Venus there are three extremely attractive and seductive gay characters, a male couple and a lesbian chanteuse, all of whom get ample screen time to make an impression on heroine Elena Martin (Audie England) as she explores her sexuality and becomes a writer of erotica. Knop co-wrote this screenplay with a female writer, Elisa M. Rothstein, who herself went on to create an erotic TV series called Women: Stories of Passion.

Naughty gay Donald (Bernard Zette) introduces Elena to the gorgeous writer Lawrence Walters (Costas Mandylor) by saying, “Beautiful, isn’t he?” and lightly slapping Lawrence’s face and pronouncing, “Dangerous!” Mandylor has the most luscious lips of all time, and England’s mouth is similarly beautiful, all pouting lower lip and drawn-on upper lip, and so their make-out sessions in Delta of Venus are momentous, and the camera makes Mandylor the abundantly fleshy sex object as they first couple on a kitchen counter near French doors, his white long underwear dropping so that England’s Elena can feel all of him and we can look at his epic nakedness from behind. When we see Elena naked from the front, Lawrence is staring at her with tender awe, like all the best King-Knop men do.

Donald’s boyfriend Miguel (Rory Campbell) gets Elena to pose nude for his life drawing class with a male model who looks much like Lawrence, a doubling that will allow Elena to unleash her imagination to write her erotic stories for an unknown male buyer. In real life, Nin dealt with a crass anonymous buyer of her erotic stories who wanted graphic sex descriptions only, whereas Knop and Rothstein improve on life by having Lawrence be the buyer of the stories, and Lawrence is far better looking than Nin’s real-life paramour Henry Miller, and surely the fantasist in Nin would have been pleased by a lot of this.

Knop and King finally deal with truly evil male desire here in the form of a Nazi named Luc (Marek Vasut) who is always hovering around Elena and waiting to defile her. “Forget about Proust…I am what you want,” Luc tells Elena in a bookshop, forcefully shutting the book she is reading; in all of King’s films it is clear that jerky-to-evil men are insecure in themselves, easily pricked for humiliation in the way they would like to humiliate others, a key insight that plays well today, just as King-Knop’s dramatization of seduction and consent holds up well to the scrutiny of today. “Say stop,” Steven Bauer says as he seduces Joan Severance in that first Red Shoe Diaries episode “Safe Sex,” and then he asks, “Do you want me to stop?” as if he means it. The good men in the King-Knop films are sexually ethical like that.

As Hitler advances through Europe conquering countries, England’s Elena in Delta of Venus fights back in her own way by opening herself to lesbian sex at an opium orgy. To Elena, her sexual fantasies are permanent in a way that real life is not, which is why she has the strength to endure giving herself up to the Nazi against a chain link fence as just another experience that might be fed into her work, her real life, her writing. “There’s a certain type of freedom that comes from pushing beyond what is acceptable,” King said in his Jump Cut interview, referring to the scene where Elena submits to the Nazi sexually. “Most of us live in a realm of manners, including myself, of what’s acceptable…there’s a freedom (some girls) seem to find past what is traditionally acceptable… I’m not sure if it’s a good thing or a bad thing, but there is a freedom.”

The ending of Delta of Venus couldn’t be more persuasively romantic as Elena says this on the soundtrack while taking her leave of Lawrence: “If I move, this person knows it. If I drop away, this person feels it. I exist in him. That is life. There’s something happening there.” Surely this is a thought that could only come from the depths of some great romance from life, a romance that goes on even after the death of King and Knop’s own death in 2019. They were collectors of objects, and some of Knop’s sculptures are enormous, so much so that she wondered if it wouldn’t be best to drop some of them into the sea to be found or not at some later point by some sailor or voyager, maybe a man like her long-time husband, who emerged from the sea like some love god and made her happy just as her adorable sophistication made him happy.

There is a silly side to King’s films, of course, especially in the group scenes where people dance and orgies begin, yet that has its sweet aspect. But critics and even audiences who enjoyed the films he made in collaboration with Knop laughed them off, maybe, because what they are saying is so nakedly sincere and hopeful. Romance was out of fashion when they made their films, and it is even more out of fashion now. It should make a comeback, and when it does, the films of Zalman King and Patricia Louisianna Knop should be claimed, re-claimed, and even used as a design for living. They have been for me.

Zalman and Pat were very original authors and their oeuvre deserves such re-assessments and whose legacy of films which revolutionised the 20th century presentation of sex and especially onscreen female desire really stands up to critical re-appraisal. Connoisseurs and cognoscenti will always recognise the pair as true artists and very real film makers of quality.